Resource Topics: mental health problems

Resources

MythBuster – Trauma and mental health in young people: Let’s get the facts straight

Introduction

Most young people will have been exposed to at least one traumatic event in their lifetime. Multiple and prolonged exposure to trauma is also common. When a young person reaches out to open up about trauma, the way that others around them respond can have a massive impact on the young person’s ability to understand and cope with their experiences. Yet some aspects of trauma remain largely misunderstood, particularly its relationship with mental health.

This mythbuster has been created for young people, their families, and carers to replace some of the most common and harmful myths about trauma in the mental health space with a better understanding of what trauma is and how it can affect young people.

Trauma can come from many different life experiences

What is trauma?

Trauma is broadly described as a deeply distressing experience that can be emotionally, mentally, or physically overwhelming for a person. It takes on many different forms and effects vary from one person to another (van der Kolk et al., 2005; Bryson et al., 2017). It is important to know that an experience does not have to be life threatening to be traumatic. Approximately two thirds of young people will have been exposed to a traumatic event by the time they turn 16 (Copeland et al., 2007). Experiencing a traumatic event can potentially affect both their current and future mental health.

What types of events cause trauma?

Trauma can arise from many different life experiences. Some examples of different types of trauma are listed below:

Direct and indirect trauma

Some types of trauma are called ‘direct trauma’, and others are called ‘indirect trauma’ (May & Wisco, 2016). A ‘direct trauma’ is experienced first-hand or by witnessing a trauma occurring to another person. An ‘indirect trauma’ comes from hearing or learning about another person’s trauma second-hand.

Single event trauma

Single event trauma is related to a single, unexpected event, such as a physical or sexual assault, a fire, an accident, or a serious illness or injury. Experiences of loss can also be traumatic, for example, the death of a loved one, a miscarriage, or a suicide.

Complex trauma

Complex trauma is related to prolonged or ongoing traumatic events, usually connected to personal relationships, such as domestic violence, bullying, childhood neglect, witnessing trauma, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, or torture.

Vicarious trauma

Vicarious trauma can arise after hearing first-hand about another person’s traumatic experiences. It is most common in people working with traumatised people, such as nurses or counsellors. Young people may also experience vicarious trauma through supporting a loved one who is traumatised (e.g. a parent or a friend).

Trans- or intergenerational trauma

Trans- or intergenerational trauma comes from cumulative traumatic experiences inflicted on a group of people, which remain unhealed, and affect the following generations (Hudson, Adams & Lauderdale, 2016). It is most common in young people from refugee or migrant families.

Anyone can experience trauma, regardless of their age or social/cultural background

Who experiences trauma?

Some young people are at higher risk of being victimised, abused, marginalised, excluded, and/or experiencing unsafe situations that leave them vulnerable to potentially traumatic experiences. Young people who are more likely to have experienced trauma include those in out-of-home care, in the juvenile justice system, those experiencing homelessness, young refugees or asylum seekers, and young people working in emergency services (Orygen, 2017). However, it is very important to understand that anyone can experience trauma, regardless of their age or social/cultural background.

How do our perceptions of traumatic events change as we age?

When trying to understand the impact trauma has on the lives of young people, it is important to understand the way we make sense of and respond to trauma as we age. During childhood we are more sensitive to our environment, so how we view threats can be quite different to the way adults view threats (Odgers & Jaffee, 2013). For example, during COVID, parents may be distressed about the safety of their children, the loss of their livelihood, and the impact on their community. On the other hand, children may be most distressed about separation from their extended family and school friends, and the disruption of their daily routines (The Australian Child and Adolescent Trauma Loss and Grief Network, 2010). This can mean that adults might be confused or unable to relate to their child’s response to a traumatic event. Likewise, a child may also be confused by their parents’ reactions and/ or why they might not be feeling or responding to an event in the same way.

Young people and children process trauma differently

As their brains are still developing, children process trauma differently compared to adults. This means that the types of things that children interpret as traumatic, and how they understand them, can be very different to adults.

When looking back at traumatic experiences in childhood, it can be hard to understand the confusing emotions and reactions experienced at the time. A young person might look back and think that they should have been able to understand things ‘better’ or cope ‘better’. This can lead to strong and difficult feelings like anger, guilt, and shame.

When a young person is caught up in this way of thinking, they may cope with an ‘adult’ response. In other words, they attempt to look back on their experiences in childhood through the lens of an adult. By doing this, it is easy to forget that the trauma happened to a child, who has much less ability and life experience, to help them process their trauma and seek support.

The way we make sense of and respond to trauma changes as we age

How does trauma affect young people?

Short-term effects

The short-term effects of trauma are often described as normal reactions to abnormal events (Jones & Wessely, 2007), and can include:

- fear

- guilt

- anger

- isolation

- helplessness

- disbelief

- emotional numbness

- sadness, confusion

- flashbacks or persistent memories and thoughts about the event (van der Kolk, 2000)

It is really important to know that these are normal and healthy reactions to trauma. These can last for up to a month after the trauma has occurred, and can slowly reduce over time.

Long-term effects

Sometimes these strong emotions, thoughts, and memories can continue and even worsen over time. This can overwhelm a young person and have damaging effects on their life and course (e.g. their wellbeing, relationships, and their ability to work and/or study) (Orygen, 2017). Some traumas, such as those occurring in childhood, may have effects that only become clear later in life (Felitti, 2002). In the long-term, there is a strong relationship between trauma and poor mental and/or physical health outcomes; however, in many cases young people can bounce back with the right support (Iacoviello & Charney, 2014; Felitti et al., 1998). Additionally, in some situations, young people can draw personal strength from their struggle with trauma and experience a feeling of positive growth (Meyerson et al., 2011).

Developmental effects

Being exposed to trauma when individuals are very young can change how their brain grows and negatively affect their ability to learn (Whittle et al., 2013; Malarbi er al., 2017). Experiencing high levels of stress at a young age can also increase risk-taking behaviours in adolescence and early adulthood, which can lead to poor physical health later in life (Felitti, 2002).

What is post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD?

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the most commonly talked about trauma-related diagnosis. Symptoms include having intrusive memories of the traumatic event, increased stress, avoidance of situations and/or people associated with the trauma, and increased negative thoughts (American Psychiatric Society, 2013). These symptoms impact a person’s ability to keep up with their day-to-day life and make it hard for them to focus on work and/or study and other tasks.

In Hong Kong, an increase of people experiencing PTSD symptoms has risen to approximately more than 30% in 2019. PTSD can also cause problems with a person’s relationships with others (Koenen et al., 2017), and symptoms may differ between children, adolescents, and adults (Mikolajewski, Scheeringa & Weems, 2017). Thus, it is really important to get help early if you are struggling to cope after experiencing trauma because evidence shows that the sooner help is sought, the lower the risk of developing PTSD (Gillies et al., 2016).

Evidence shows that the sooner help is sought, the lower the risk of developing PTSD

What are the most common myths about trauma?

Traumatic events and a young person’s reaction to them vary a lot. They can vary between people (e.g. some people may be more sensitive to traumatic experiences than others), within the same person over time, or differ depending on the type of traumatic event the person has experienced.

This can make it difficult for us to have a shared understanding of what trauma is and how it can affect people. If we feel confused or uncertain about what trauma is and how it can affect someone, it would be very easy to end up believing in common and unhelpful myths instead.

Below are some of the common myths surrounding trauma and the reasons why these myths are harmful and untrue.

MYTH: “Everyone who has mental ill-health has experienced trauma”

This myth is particularly harmful because young people who have not experienced trauma, but who are struggling with their mental health may feel that they have no right to feel how they do, or become very confused about how they are interpreting their experiences. They may also worry that if they seek support, everyone would automatically assume they have experienced a type of trauma.

Just because a young person is experiencing mental ill-health, this does not necessarily mean that they have gone through trauma. There are many risk factors that contribute to the beginning of mental ill-health. These can be environmental, genetic, social, and cultural in nature (Kieling et al., 2011).

Mental ill-health can start without a specific event ‘tipping a person over the edge’. In fact, mental ill-health is often triggered by a build-up of a number of smaller stressful events rather than one big traumatic event (Fox & Hawton, 2004). Even though trauma is linked to a higher chance of poor mental health, it is important to remember that the causes of mental ill-health in young people are very complex and differ from person to person (Guina et al., 2017; Paus, Keshavan & Giedd, 2008).

It is really important to know that developing mental health problems after trauma is not a sign of weakness

MYTH: “Everyone who has experienced trauma will develop mental ill-health”

Most people who experience trauma do not develop mental ill-health as a consequence (Sayed, Iacoviello & Charney, 2015). Many factors influence whether or not a young person develops mental ill-health after experiencing trauma. These include the severity and type of trauma, the support available, how easily they can access this support, past traumatic experiences, family history, and physical health (Iacoviello & Charney, 2014; Sayed, Iacoviello & Charney, 2015; Brewin, Andrews & Valentine, 2000).

It is completely normal to experience strong or overwhelming emotions after a traumatic experience, but it is when these symptoms last a long time, worsen overtime, or cause other problems (e.g. using substances to cope) that mental health difficulties are likely to arise. It is really important to know that developing mental health problems after trauma is not a sign of weakness, nor does it reflect anything about you personally. It is simply a sign that you may need some extra support to recover from the effects of your experiences.

MYTH: “It’s my fault”

Trauma can happen to anyone, and if you are a victim of trauma, this does not mean that you are to blame for what happened to you. ‘It’s my fault’ is a common thought after experiencing trauma, and it is completely normal to feel shame, guilt, and/or self-blame after these experiences. Even though you may feel this way, it does not mean you deserve these feelings, and a huge part of recovery is working to overcome them.

These types of emotions are particularly common in young people who have been traumatised by another person (e.g. through sexual abuse, physical abuse, bullying, or violent crime). In cases of trauma resulting from abuse, it is important to understand that abuse comes from the needs and motivations of the perpetrator, not the individual. Being able to work through these strong emotions of self-blame, guilt, and/or shame is essential to recovery. This means it is very important to find the right help to support you through this process.

Traumatic events are sometimes singular and life threatening, but many are more complex.

MYTH: “Only bad things come out of traumatic experiences”

Struggling through traumatic experiences often changes the way a person views the world and people around them. A lot of the time, the changes in thoughts are negative (e.g. the world seems scarier, or people seem less trustworthy). However, in some situations, with the right support, and time to heal, a person may also draw strength and positive change from surviving a traumatic event.

When this happens, it is described as ‘post-traumatic growth’ (Linley & Joseph, 2004; Clay, Knibbs & Joseph, 2009; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). When someone experiences post-traumatic growth, they may gain a greater appreciation for life, a feeling of greater personal strength, a deeper connection to others, and even gain new ideas about the path they see their life taking in the future (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Research shows that post-traumatic growth is hugely influenced by many psychological, social, and environmental factors in a young person’s life (Meyerson et al., 2011). How each of us reacts to traumatic experiences is deeply linked to these factors, and our different reactions do not make us ‘weaker’ or ‘stronger’ compared to others.

MYTH: “Your life must be threatened for an event to be traumatic”

Traumatic experiences take many different forms (Weiss & Gutman, 2017). There does not have to be one defining event that makes something traumatic. It is true that traumatic events are sometimes singular and life threatening, but others are more complex. Many people experience trauma through ongoing or prolonged exposure to events such as abuse, neglect, and bullying. Others may experience trauma vicariously through encountering another person’s traumatic experiences first-hand.

MYTH: “PTSD is the most common response to trauma”

Although post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the most commonly talked about trauma-related mental illness, it is not the most common mental health diagnosis among people who have experienced trauma. There are many ways that trauma can affect mental health in young people (Sayed, Iacoviello & Charney, 2015). In fact, for most young people, PTSD only captures a small aspect of their mental health state after trauma (van der Kolk & Courtois, 2005). Young people who have experienced trauma can develop a wide range of mental health problems, without developing PTSD (Odgers & Jaffee, 2013). These can include depression (Widon, Du Mont & Czaja, 2007), anxiety (Fernandes & Osorio, 2015), complex PTSD (Resick et al., 2012), borderline personality disorder (Ball & Links, 2009), substance abuse disorders (Stevens, Murphy & McKnight, 2003), eating disorders (Pignatelli et al., 2017), psychosis (Bendall et al., 2008), and suicide-related behaviours (Miller et al., 2013).

Take home messages

- If you have experienced trauma, you are not alone. Trauma in young people is very common and it is important for family, friends, and mental health professionals to be aware of this.

- Traumatic events can be one off (e.g. car accident, sexual assault), ongoing/prolonged (e.g. childhood sexual abuse, bullying, emotional or physical abuse), or experienced second-hand (e.g. witnessing family violence). Any type of trauma has the potential to be very damaging to a young person’s mental health.

- Often young people who have been abused or neglected feel at blame for what has happened to them – they may feel it was their fault, or that they ‘brought it on’ or ‘asked for it’. If you are in this situation, it is very important to know that you are not to blame, no matter how strong the feelings of guilt or shame may be.

- There is no one uniform or ‘right’ way to respond to a traumatic event. Responses to trauma are highly variable. Different people may react very differently, even to the same situation.

- Young people experiencing mental ill-health have not necessarily experienced trauma, and this does not make their mental health difficulties any less ‘real’ or ‘legitimate’.

- Trauma does not always lead to mental ill-health in young people. Many young people exposed to trauma will make a full recovery without needing mental health intervention.

- Experiencing mental health difficulties related to trauma is not a sign of weakness or failure.

- Trauma can lead to a wide range of mental health difficulties, not just PTSD. These can include anxiety, depression, substance abuse, borderline personality disorder, and eating disorders. It is important to get support from a health professional for any of these difficulties.

- It is possible to recover from mental health difficulties related to trauma.

Help is at hand

Support is a huge protective factor against ongoing mental health difficulties related to trauma. Sometimes people can try to cope with the effects of trauma alone, even though reaching out for support can be hugely beneficial. Some young people might feel an overwhelming sense of self-blame or shame and might not be aware of or understand the effects of trauma, making it even harder to seek support.

Seeking help from someone you know

It is really important to try to find someone you can talk to about what’s going on for you. Seeking support for trauma recovery does not make a person ‘weak’, in fact it is a brave step to take on the road to recovery. Opening up about traumatic events can be daunting, making it very important to find someone you feel comfortable with and can trust to talk to. This person could be a family member, friend, or school counsellor.

Seeking professional help

Some young people may not feel comfortable opening up to people in their personal lives and may prefer to seek help through a mental healthcare professional. In terms of seeking professional help, a good place to start is with your doctor, a counsellor, or through a visit to your closest local support group.

A number of helplines in Hong Kong can be found here:

- Emergency hotline: 999

- The Samaritans 24-hour hotline (Multilingual): (852) 2896 0000

- Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2389 2222

- Suicide Prevention Services 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2382 0000

- OpenUp 24/7 online emotional support service (English/Chinese): www.openup.hk

More hotlines and resources can also be found here:

Want to know more?

Some helpful resources about trauma and its effects include:

- Asking for Help: When it’s time to talk about your mental health- Coolminds and Charlie Waller Memorial Trust (CWMT) UK factsheet

- Seeking help and what to expect- Coolminds factsheet

- Discrimination and Mental Health: A Guide for Young People- Coolminds factsheet

- Voices of Youth: Stigma, Discrimination and Mental Health- Coolminds factsheet

Supporting someone who has experienced trauma can be emotionally overwhelming, making it equally important to look after yourself. If you are concerned about the wellbeing of someone close to you, it is important to reach out for additional help.

Some highly recommended websites that offer more information on how to support to someone affected by trauma include:

- Samaritans Hong Kong

- Samaritans Befrienders Hong Kong

- The Zubin Foundation- Ethnic Minority Well-being Centre (EMWC)

- Christian Action (Woo Sung Centre)

- Yang Memorial Methodist Social Service- Yau Tsim Mong Family Education and Support Centre

- The Salvation Army Youth, Family and Community Services

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder – Institute of Mental Health Castle Peak Hospital

- BGCA – What is Trauma?

References

1. van der Kolk, BA, et al. 2005, ‘Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 18, no. 5. pp. 389–399.

2. Bryson, SA, et al. 2017, ‘What are effective strategies for implementing trauma-informed care in youth inpatient psychiatric and residential treatment settings? A realist systematic review’, International Journal of Mental Health Systems, vol. 11, pp. 36.

3. Copeland, WE, et al. 2007, ‘Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood’, Archives of General Psychiatry, vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 577–584.

4. Hudson, CC, Adams, S & Lauderdale, J 2016, ‘Cultural expressions of intergenerational trauma and mental health nursing implications for US healthcare delivery following refugee resettlement: an integrative review of the literature’, Journal of Transcultural Nursing, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 286–301.

5. May, CL & Wisco BE 2016, ‘Defining trauma: how level of exposure and proximity affect risk for posttraumatic stress disorder’, Psychological Trauma, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 233–40.

6. Orygen The National Centre of Excellence for Youth Mental Health, Youth Mental Health Policy Briefing: Trauma and Youth Mental Health. 2017, Orygen: Melbourne.

7. Odgers, CL & Jaffee SR 2013, ‘Routine versus catastrophic influences on the developing child’, Annual Review of Public Health, vol. 34, no. 1. pp. 29–48.

8. The Australian Child and Adolescent Trauma Loss and Grief Network 2010, ‘How children and young people experience and react to traumatic events’, Australian National University, Canberra.

9. Jones, E & Wessely S 2007, ‘A paradigm shift in the conceptualization of psychological trauma in the 20th century’, Journal of Anxiety Disorders, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 164–175.

10. van der Kolk, B 2000, ‘Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma’, Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 7–22.

11. Felitti, VJ 2002, ‘The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult health: Turning gold into lead’, Zeitschrift Fur Psychosomatische Medizin Und Psychotherapie, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 359–369.

12. Iacoviello, BM & Charney DS 2014, ‘Psychosocial facets of resilience: implications for preventing posttrauma psychopathology, treating trauma survivors, and enhancing community resilience’, European Journal of Psychotraumatology, vol. 5.

13. Felitti, VJ, et al. 1998, ‘Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 245–258.

14. Meyerson, DA, et al. 2011, ‘Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: a systematic review’, Clinical Psychology Review, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 949–964.

15. Whittle, S, et al. 2013, ‘Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology affect brain development during adolescence’, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 52, no. 9, pp. 940–952.

16. Malarbi, S, et al. 2017, ‘Neuropsychological functioning of childhood trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis’, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 72, pp. 68–86.

17. American Psychiatric Society 2013, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn, American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington.

18. Koenen, KC, et al. 2017, ‘Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health Surveys’, Psychological Medicine, vol. 47, no. 13, pp. 2260–2274.

19. Mikolajewski, AJ, Scheeringa, MS & Weems, CF 2017, ‘Evaluating diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, posttraumatic stress disorder diagnostic criteria in older children and adolescents,’ Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 374–382.

20. Gillies, D, et al. 2016, ‘Psychological therapies for children and adolescents exposed to trauma’, Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, vol. 10, pp. Cd012371.

21. Kieling, C, et al. 2011, ‘Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action’, The Lancet, vol. 378, no. 9801, pp. 1515-1525.

22. Fox, C & Hawton K 2004, Deliberate self-harm in adolescence, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London 23. Guina, J, et al. 2017, ‘Should posttraumatic stress be a disorder or a specifier? Towards improved nosology within the DSM categorical classification system’, Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 66

23. Guina, J, et al. 2017, ‘Should posttraumatic stress be a disorder or a specifier? Towards

improved nosology within the DSM categorical classification system’, Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 66

24. Paus, T, Keshavan, M & Giedd, JN 2008, ‘Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence?’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 947-57

25. Sayed, S, Iacoviello, BM & Charney, DS 2015, ‘Risk factors for the development of psychopathology following trauma’, Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 612

26. Brewin, CR, Andrews, B & Valentine, JD 2000, ‘Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults’, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, vol. 68, no. 5, pp. 748-66

27. Linley, PA & Joseph S 2004, ‘Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 11-21

28. Clay, R, Knibbs, J & Joseph, S 2009, ‘Measurement of posttraumatic growth in young people: a review’, Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 411-22

29. Tedeschi, RG & Calhoun LG 2004, ‘Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence’, Psychological Inquiry, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1-18

30. Weiss, KJ & Gutman AR 2017, ‘Testifying About Trauma: A Call for Science and Civility’, Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 2-6

31. van der Kolk, BA & Courtois CA 2005, ‘Editorial comments: Complex developmental trauma’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 385-388

32. Widom, CS, Du Mont, K & Czaja, SJ 2007, ‘A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up’, Archives of General Psychiatry, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 49-56

33. Fernandes, V & Osorio FL 2015, ‘Are there associations between early emotional trauma and anxiety disorders? Evidence from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis’, European Psychiatry, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 756-764

34. Resick, PA, et al. 2012, ‘A critical evaluation of the complex PTSD literature: implications for DSM-5’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 241-251

35. Ball, JS & Links PS 2009, ‘Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: evidence for a causal relationship’, Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 11, no. 1, pp 63-68

36. Stevens, SJ, Murphy, BS & McKnight, K 2003, ‘Traumatic stress and gender differences in relationship to substance abuse, mental health, physical health, and HIV risk behavior in a sample of adolescents enrolled in drug treatment’, Child Maltreatment, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 46-57

37. Pignatelli, AM, et al. 2017, ‘Childhood neglect in eating disorders: A systematic review and metaanalysis’, Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, vol. 18, no.1, pp. 100-115

38. Bendall, S et al. 2008, ‘ Childhood trauma and psychotic disorders: a systematic, critical review of the evidence’, Schizophrenia Bulletin, vol. 34, pp. 568-579

39. Miller, AB, et al. 2013, ‘The Relation Between Child Maltreatment and Adolescent Suicidal Behavior: A Systematic Review and Critical Examination of the Literature’, Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 146-172

Disclaimer

This information is not medical advice. It is generic and does not take into account your personal circumstances, physical wellbeing, mental status or mental requirements. Do not use this information to treat or diagnose your own or another person’s medical condition and never ignore medical advice or delay seeking it because of something in this information. Any medical questions should be referred to a qualified healthcare professional. If in doubt, please always seek medical advice.

Mythbuster writers

Anna Farrelly-Rosch

Dr Faye Scanlan

Youth contributors

Sarah Langley – Youth Research Council

Somayra Mamsa – Youth Research Council

Roxxanne MacDonald – Youth Advisory Council

Clinical consultant

Dr Sarah Bendall

First published as ‘Trauma and mental health in young people: Let’s get the facts straight’ by Orygen, 2018.

Resources

Anxiety in Young Adults

Anxiety is the most common mental illness in young adults.

According to a survey by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups that interviewed 4,443 secondary school students between September and October 2020, nearly 22% of secondary students in Hong Kong displayed signs of anxiety.

How we feel and think is central to how we live our daily lives. That’s why it’s important that we understand what anxiety is.

What is anxiety?

Anxiety is a feeling of unease such as worry or fear that can be mild or severe. Everyone experiences anxiety at some point in their life especially in high pressure situations but anxiety disorder is something more serious.

What is anxiety disorder?

Anxiety disorder is a mental illness when you have persistent, excessive and uncontrollable anxious feelings that causes significant disruption to your day-to-day functioning.

How does it affect your daily life?

Anxiety can prevent you from being yourself at school, work, family get-togethers, and other social situations that might trigger or worsen your symptoms. These may include (but aren’t limited to) frequent and excessive worry, poor concentration, sleep disturbance, muscle tension, fatigue, shortness of breath, avoidance and social withdrawal.

How to cope with anxiety?

- Establish and maintain a healthy routine: get enough sleep, have balanced meals and continue to exercise regularly.

- Spend time with your friends and family even if this is done remotely (e.g. by phone, text or FaceTime).

- Find resources at your school: school counsellors, social workers and academic advisors.

- If you are struggling, seek professional help.

How to support your peers who are coping with anxiety?

You could check-in to see how they’re doing and offer to accompany them to seek support. Help them regain self-confidence and feel accepted for who they are. When they feel ready, encourage them to meet new people and use their experiences to help others, which can break the stigma of mental ill-health.

Special thanks to Island School student Nicole Cheng who granted permission to use and adapt her work.

Resources

Seeking Help and What to Expect

Who to seek help from

Congratulations! If you are reading this section, that means you’re ready for change. But we know that seeking help can be confusing and overwhelming so let’s start by understanding what different mental health professionals do and how they can help. Here’s a guide on the range of mental health professionals that you may find:

General practitioner (GP)

General practitioners, also known as family doctors, are medical doctors specializing in general medicine. They are also the doctors you see when you are feeling physically unwell. Your GP is often the first professional you would see when you are struggling with your mental health. They are trained to assess, diagnose and treat mild to moderate mental health conditions. GP’s can prescribe medications and provide preventative care and health education. They can also refer and direct you to the appropriate specific mental health professionals. Seeing your GP is the best first step to getting help.

Psychiatrists

Psychiatrists are licensed medical doctors who specialize in mental health. They are trained to assess, diagnose and treat mental health disorders, primarily through prescribing and monitoring medication treatment, they often do not provide “talk therapy”. Your visit with a psychiatrist may include a blood test, a physical assessment and a risk assessment. Psychologists can work at hospitals, private offices, or community health centres.

Mental health nurse

A psychiatric nurse is a registered nurse with specialised training in mental health. A psychiatric nurse assesses, supports and advocates for care. They typically assist and work with psychiatrists working in the public health care system. As part of their role they follow up with patients regarding medications, and needed supports.

Social workers

Social workers are dedicated to helping people navigate and solve issues in their lives which may be caused by relationship problems, adjustment issues, traumatic events, or disabilities, etc. Through case management, they redirect clients to resources that best support them. Social workers can be found in a variety of settings, such as schools, private offices, hospitals, community health centres, and non-profit organisations.

Counsellors

Counsellors are masters-level professionals. They aim to help people to understand the complex social welfare system and help to access resources which support a person’s wellbeing. They also receive basic counselling training and may be able to provide counselling to people in distress. Counsellors can be found at schools, hospitals, community health centres, and in private practice.

So what’s the difference between a counsellor and a psychologist?

Psychologists often have more formal education who are trained to diagnose and treat specific mental illnesses, whereas counsellors help people to process and cope with their mental health struggles.

Clinical psychologists

In general, psychologists have doctoral training qualifications; however, they are not medical doctors and do not prescribe medication. Clinical psychologists are specially trained to diagnose and treat mental illnesses through talk therapy, and they are the most common type of psychologist you would see for a mental health issue.

Educational psychologists

Educational psychologists are trained in teaching and education, focusing on learning-related issues. They work with students, parents, teachers, and support professionals to help students in the school setting. Psychologists can be found in places such as private offices, hospitals, and schools.

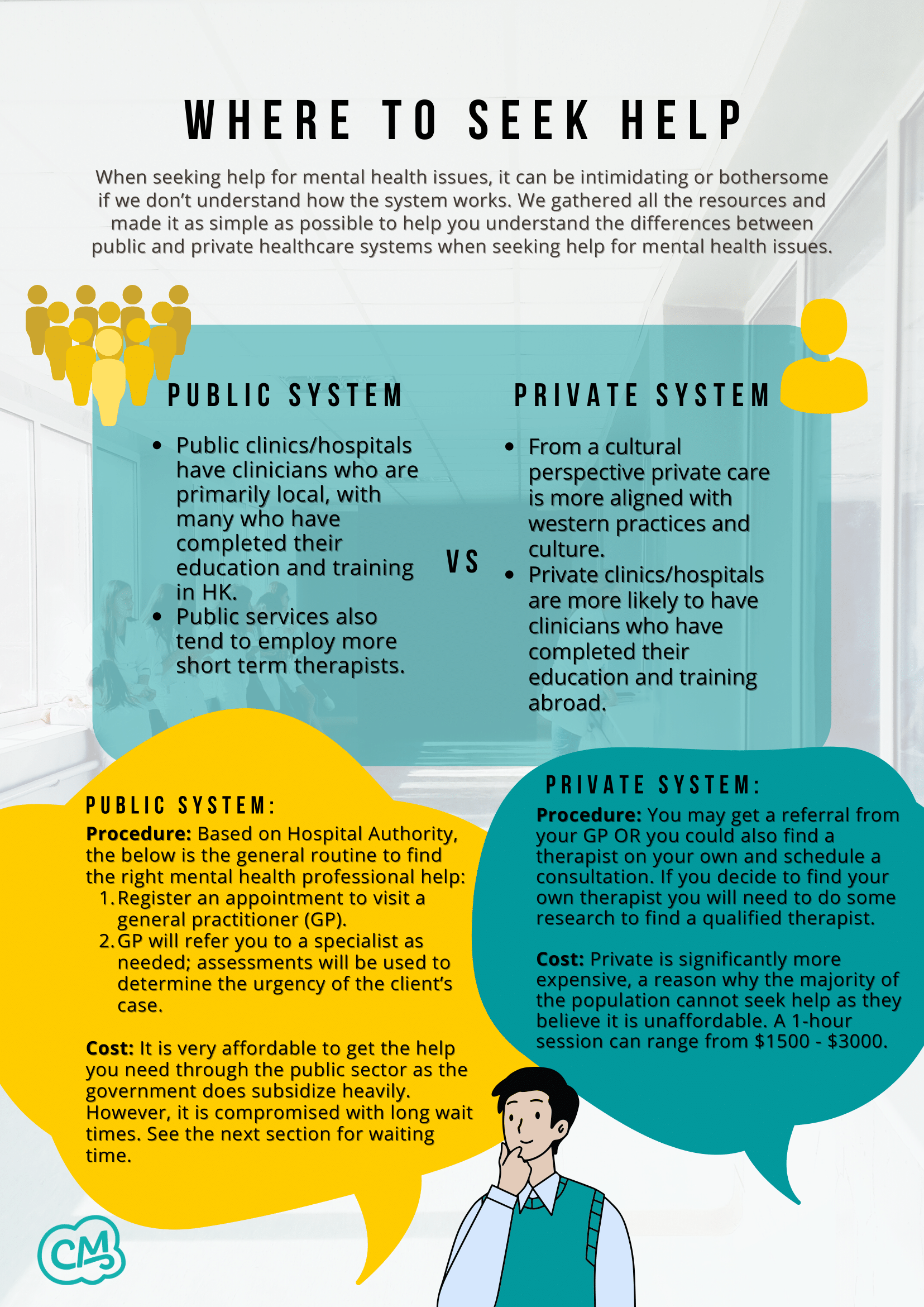

Where to seek help

When seeking help for mental health issues, it can be intimidating or bothersome if we don’t understand how the system works. We gathered all the resources and made it as simple as possible to help you understand the differences between public and private healthcare systems when seeking help for mental health issues.

Public system

- Public clinics/hospitals have clinicians who are primarily local, with many who have completed their education and training in HK.

- Public services also tend to employ more short term therapists.

- Procedure: Based on Hospital Authority, the below is the general routine to find the right mental health professional help:

- Register an appointment to visit a general practitioner (GP).

- GP will refer you to a specialist as needed; assessments will be used to determine the urgency of the client’s case.

- Cost: It is very affordable to get the help you need through the public sector as the government does subsidise heavily. However, it is compromised with long wait times. See the next section for waiting time.

Private system

- From a cultural perspective private care is more aligned with western practices and culture.

- Private clinics/hospitals are more likely to have clinicians who have completed their education and training abroad.

- Procedure: You may get a referral from your GP OR you could also find a therapist on your own and schedule a consultation. If you decide to find your own therapist you will need to do some research to find a qualified therapist.

- Cost: Private is significantly more expensive, a reason why the majority of the population cannot seek help as they believe it is unaffordable. A 1-hour session can range from $1500 – $3000.

What to expect

So what should I expect before I head for my first session?

Before you head to your first session, remember this initial visit to a professional is no different than a first appointment with a new general practitioner (or family doctor). It may be uncomfortable to talk about some of your concerns and experiences but it is an important first step to getting better.

What will we talk about during first session?

However, a small detail that could cause anxious feelings is the fact that your relationship with a therapist is important to help your recovery journey. It could be intimidating to spill all your deepest and “darkest” secrets to a stranger you barely know and the thought of bailing might even cross your mind. Just know that every therapist actually understands the nerves of your feelings and they’ll try their best to soothe you and make you feel comfortable. Regardless, whether you’re full of nerves or can’t wait to start blabbing away on that couch, your new therapist will be ready for you and perfectly able to meet you where you’re at. And if all you want to talk about during that first session is how nervous you are or how much you don’t want to be there, then that’s totally fine.

How does talking with a professional help my condition?

There are many types of “talk therapies” available depending on the mental health issues you are struggling with. One of the most commonly used one is Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), which focuses on challenging and changing unhelpful thought and behaviour patterns, while improving emotional regulation and developing helpful coping strategies.

So what will happen in the first session?

In your first session, you may be asked about:

- Your mood, thoughts and behaviours

- Your lifestyle (friendships, school, intimate relationships, family relationships)

- Any recent events in your life that might be affecting your wellbeing

- Any changes to your sleep, diet and daily activities

- Your medical history

- If you are seeing a GP or a psychiatrist they may take your blood pressure, listen to your heart, as well as doing blood tests to explore any physical issues that may contribute to your emotions and behaviours

What about with a specific mental health professional? What questions do they ask?

With a specific mental health professional you may be asked:

- How long have you been experiencing these problems or issues?

- What have you tried to do to cope with it?

- What do you think the trigger could be?

- How often are you suffering from it?

- What was your life like before this issue or problem was present?

Are there any other questions they would ask? What should I do if I don’t want to answer certain questions?

There are many other questions that a therapist will ask once you start talking about your presenting problem. They’ll start out pretty general and get more detailed as the sessions move forward.

You’ll be asked to think about what’s going on and how you’re experiencing it. Some of it will feel really personal. A therapist needs to try to understand the triggers and causes of your struggles in order to figure out how they can help. If you ever feel like you don’t want to answer a question quite yet, speak up and say so.

With certain types of therapies or cases it may involve some homework. Just be aware that often therapy is most effective when you also put in the work outside of the office as well.

Often, a therapist will ask you what your goal is for therapy. It’s helpful to figure that out upfront. But it’s also okay if you don’t have a specific goal in mind when you start. There won’t be any pressure to try and define it early on.

- Types of therapy

- Confidentiality

- Your conversations with your therapist are confidential. However, if they are concerned about your safety or the safety of others they will talk to you about disclosing to a trusted supporter (usually your parent/guardian if that is safe).

- Goals of therapy

- Give you the tools and strategies for navigating whatever is going on in your life — from stress or relationship issues to managing a mental health diagnosis

- Process of therapy journey

- Length of treatment

- Touch on it may get worse before it gets better

- Mention every case is different, just because you are diagnosed with a psychological disorder does not indicate you can be generalised and treated like any other client that has the same condition as you.

- Relapse

- We don’t expect recovery to happen overnight, and sometimes it’ll bounce back, making you think you haven’t made any progress. But this is certainly not the case. One thing we want you to take away from reading this booklet is to take the first step of speaking up and seeking help.

Emergency support

If you are experiencing strong levels of distress or trauma which are interfering with your life, remember that you do not have to face it alone, and that help is available.

For emergency support, please contact the hotlines below:

Emergency hotline: 999

The Samaritans 24-hour hotline (Multilingual): (852) 2896 0000

Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2389 2222

Suicide Prevention Services 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2382 0000

OpenUp 24/7 online emotional support service (English/Chinese): www.openup.hk

More support services can be found here: https://www.coolmindshk.com/en/emergency-hotlines/

More non-urgent support services can be found here: https://www.coolmindshk.com/en/communitydirectory/

Resources

Signs of Depression

We would like to acknowledge the Charlie Waller Memorial Trust (CWMT) UK for these resources and for allowing us to adapt this. For the original version of this resource, please refer to the CWMT website: www.cwmt.org.uk

Resources

Bipolar Disorder Symptoms

This resource booklet has been localised for the Hong Kong context and translated to Traditional Chinese by Coolminds, a mental health initiative run by Mind HK and KELY Support Group. For more information on Coolminds, please visit www.coolmindshk.com

Thank you to the Black Dog Institute for donating their resources and for allowing us to adapt this. For the original version of this resource, please refer to the Black Dog Institute’s website: www.blackdoginstitute.org.au

What this fact sheet covers:

- What is bipolar disorder

- Sub-types of bipolar disorder

- Symptoms of bipolar disorder

- When to seek help for bipolar disorder

- Key points to remember

- Where to get more information

What is bipolar disorder?

- Bipolar disorder is the name used to describe a set of ‘mood swing’ conditions, the most severe form of which used to be called ‘manic depression’.

- The term describes the exaggerated swings of mood, cognition and energy from one extreme to the other that are characteristic of the illness.

- People with this illness suffer:

- Recurrent episodes of high, or elevated moods (mania or hypomania) and depression.

- Most experience both the highs and the lows.

- Occasionally people can experience a mixture of both highs and lows at the same time, or switch during the day, giving a ‘mixed’ picture of symptoms.

- A very small percentage of sufferers of bipolar disorder only experience the ‘highs’.

People with bipolar disorder experience normal moods in between their mood swings.

- The mood swings pattern for each individual is generally quite unique, with some people only having episodes of mania once a decade, while others may have daily mood swings.

- Bipolar disorder can commence in childhood, but onset is more common in the teens or early 20’s.

- Some people develop ‘late onset’ bipolar disorder, experiencing their first episode in mid-to-late adulthood.

Distinguishing between bipolar I and bipolar II

- Bipolar I disorder is the more severe disorder, in the sense that individuals are more likely to experience ‘mania’, have longer ‘highs’ and to have psychotic episodes and be more likely to be hospitalised.

- Mania refers to a severely high mood where the individual often experiences delusions and/ or hallucinations. The severe highs which are referred to as ‘mania’ tend to last days or weeks.

- Bipolar II disorder is defined as being less severe, in that there are no psychotic features and episodes tend to last only hours to a few days; a person experiences less severe highs which are referred to as ‘hypomania’ and depression but no manic episodes and the severity of the highs does not usually lead to hospitalisation.

- Hypomania literally translates into ‘less than mania’. It describes a high that is less severe than a manic episode and without any delusions and/or hallucinations.

- These highs don’t last as long. While they are officially diagnosed after a four-day duration, research has shown that they may only last a few hours to a few days.

- Both women and men develop bipolar I disorder at equal rates, while the rate of bipolar II disorder is somewhat higher in females.

Symptoms of bipolar disorder

- Diagnosing bipolar disorder is often not a straightforward matter.

- Many people go for 10 years or more before their illness is accurately diagnosed.

- It is important to note that everyone has mood swings from time to time. It is only when these moods become extreme and interfere with a person’s personal and professional life that bipolar disorder may be indicated and medical assessment sought.

- There are two starting points for considering whether you might have bipolar disorder.

- Firstly, you must have had episodes of clinical depression.

- Secondly, you must have had ‘highs’, where your mood was more ‘up’ than usual, or where you felt more ‘wired’ and ‘hyper’.

- If both depression and ‘highs’ have been experienced, then the next thing to consider is whether you also experienced any of the six key features of mania and hypomania outlined below.

Key features of mania & hypomania

While it can be difficult to identify what separates normal ‘happiness’ from the euphoria or elevation that is seen in mania and hypomania, researchers at the Black Dog Institute, have identified the following distinguishing features:

- High energy levels – feeling ‘wired’ and ‘hyper’, extremely energetic, talking more and talking over people, making decisions in a flash, constantly on the go and feeling less need for sleep.

- Positive mood – feeling confident and capable, optimistic that one can succeed in everything, more creative, happier, and feeling ‘high as a kite’.

- Irritability – irritable mood and impatient and angry behaviours.

- Inappropriate behaviour – becoming over involved in other peoples’ activities, engaging in increased risk taking (i.e. by over indulging in alcohol and drugs and gambling excessively) saying and doing outrageous things, spending more money, having increased libido; dressing more colourfully and with disinhibition.

- Heightened creativity – ‘seeing things in a new light’, seeing things vividly and with crystal clarity, senses are heightened and feeling quite capable of writing the ‘next great novel’.

- Mystical experiences – believing that there are special connections between events, that there is a higher rate of coincidence between things happening, feeling at one with nature and appreciating the beauty and the world around, and believing that things have special significance.

- More extreme expressions of mania (but not hypomania) may have the added features of delusions and hallucinations.

- A number of other symptoms can indicate whether there is a likely diagnosis of bipolar disorder, particularly for those under the age of 40. These include:

- Racing thoughts (for example, feeling like you are watching a number of different TV channels at the same time, but not being able to focus on any)

- Sleeping a lot more than usual

- Feeling agitated, restless and/or incredibly frustrated.

When to seek help for bipolar disorder

- If you have experienced an episode of mania or hypomania, or have taken the Black Dog Institute’s Bipolar Disorder Self-Test, linked under the resources at the end of this fact sheet, and are concerned about your results, it is advisable to seek professional assessment by a mental health practitioner.

- The first step is to arrange a consultation with your doctor. They will provide an assessment and, where necessary, refer you to a psychiatrist for further treatment.

- Bipolar disorder is not an illness which goes away of its own accord, but one which often needs long-term treatment. Accurately diagnosing bipolar disorder is a task for the mental health professional.

- Some people with bipolar disorder can become suicidal. It is very important that talk of suicide be taken seriously and for such people to be treated immediately. In an emergency you can go straight to your local hospital’s emergency department for help, or dial 999.

Key points to remember

- Bipolar disorder is an illness involving exaggerated swings of mood and energy from one extreme to the other, usually involving alternating periods of depression and mania or hypomania.

- The pattern of mood swings for each individual is quite unique.

- The six features of mania and hypomania are:

- High energy levels

- Positive mood

- Irritability

- Inappropriate behaviour

- Heightened creativity

- Mystical experiences

- For people under the age of 40, other symptoms of bipolar disorder may include sleeping a lot more than usual, feeling agitated, restless and/or incredibly frustrated.

- Accurately diagnosing bipolar disorder is a task for a skilled mental health practitioner.

- If symptoms of bipolar disorder are suspected it’s best to first see a doctor, who will likely refer you to a psychiatrist.

- People with bipolar disorder can become suicidal. Talk of suicide should be taken seriously and immediate help should be sought from a doctor or other mental health professional.

Contact Us

Coolminds

Email: hello@coolmindshk.com

Black Dog Institute

Email: blackdog@blackdog.org.au

Where to get more information and support

Black Dog Institute – “Bipolar Disorder Self-Test”

Mind Hong Kong – “What Is Bipolar Disorder?”

Bilingual Telephone Hotlines

Hospital Authority Mental Health 24-hour Hotline: 2466 7350

Social Welfare Department Hotline: 2343 2255

Chinese-Only Telephone Hotlines

Youth Outreach 24-hour hotline service: 90881023

The Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups “Youthline” hotline (available Mon-Sat, 2pm-2am): 27778899

Resources

Signs & Symptoms of Anxiety

This resource booklet has been localised for the Hong Kong context and translated to Traditional Chinese by Coolminds, a mental health initiative run by Mind HK and KELY Support Group. For more information on Coolminds, please visit www.coolmindshk.com

Thank you to the Black Dog Institute for donating their resources and for allowing us to adapt this. For the original version of this resource, please refer to the Black Dog Institute’s website: www.blackdoginstitute.org.au

What this fact sheet covers:

- When anxiety is a problem

- Types of anxiety disorders

- Signs and symptoms of anxiety

Everyone experiences anxiety

Feeling anxious in certain situations can help us avoid danger, triggering our ‘fight or flight’ response. Sometimes though, we can become overly worried about perceived threats – bad things that may or may not happen. When your worries are persistent or out of proportion to the reality of the threat, and get in the way of you living your life, you may have an anxiety disorder.

In Hong Kong,

- Over half of the university students show symptoms of an anxiety disorder, according to research conducted by the University of Hong Kong in 2016

- According to a 2018 survey by Hong Kong Playground Association, over a third of young people scored moderate to extremely severe on the Anxiety scale (of the DASS21)

When does anxiety become a problem?

It’s normal to feel anxious in high pressure situations such as:

- A job interview

- When you’re speaking in public

- When you’re experiencing change in your life or work environment and you’re uncertain what the future will hold.

To a degree, this anxiety can help us, making us stay focused and alert.

When we’re very anxious, we have intense feelings of worry or distress that are not easy to control. Anxiety can interfere with how we go about our everyday lives making it hard to cope with ‘normal’ challenges.

Anxiety becomes a problem when you start to feel anxious most of the time and about even minor things, to the point where your worry is out of control and interfering with your day to day life.

What are anxiety disorders?

Anxiety disorders are a mix of:

- Psychological symptoms: frequent or excessive worry, poor concentration, specific fears or phobias e.g. fear of dying or fear of losing control

- Physical symptoms: fatigue, irritability, sleeping difficulties, general restlessness, muscle tension, upset stomach, sweating and difficulty breathing

- Behavioural changes: including procrastination, avoidance, difficulty making decisions and social withdrawal

Severe anxiety is a feature of a group of mental health disorders including:

- Generalised anxiety disorder

- Social phobia

- Specific phobia

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Panic disorder

- Separation anxiety disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Other types of anxiety disorders include:

- Substance/medication-induced anxiety disorder

- Anxiety disorder due to a medical condition

It’s important to seek help to manage severe anxiety. There are many effective treatments for anxiety, and you can feel better.

Factors for developing anxiety

There is a range of contributing factors for developing anxiety. The factors could be:

- Biological – genes (family history)

- Personality traits

- Brain chemistry

- Life events, such as trauma and long-term stress

- A combination of above factors

Signs and symptoms

While there are many types of anxiety disorder, there are some common signs and symptoms.

You might be feeling:

- Very worried or afraid most of the time

- Tense and on edge

- Nervous or scared

- Panicky

- Irritable, agitated

- Worried you’re going crazy

- Detached from your body

- Feeling like you may vomit

You may be thinking:

- ‘Everything’ is going to go wrong’

- ‘I might die’

- ‘I can’t handle the way I feel’

- ‘I can’t focus on anything but my worries’

- ‘I don’t want to go out today’

- ‘I can’t calm myself down’

You may also be experiencing:

- Sleep problems (can’t get to sleep, wake often)

- Pounding heart

- Sweating

- ‘Pins and needles’

- Tummy aches, churning stomach

- Lightheadedness, dizziness

- Twitches, trembling

- Problems concentrating

- Excessive thirst

When these constant repetitive thoughts and feelings take over, we can:

- Feel overwhelmed

- Lose sleep

- Feel exhausted

- Start to avoid social situations

Some of these symptoms can also be signs and symptoms of other medical conditions, so it’s always best to see a doctor so they can check them properly.

There is an online Anxiety Self-test on the Black Dog Institute website.

Diagnosis

To be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, a combination of symptoms

- Is present on most days for more than six months

- Interferes with your ability to function at work or at home

It is common to experience a low mood secondary to excessive worry and the two conditions – clinical depression and anxiety disorder – can occur at the same time.

It’s important to get help to treat anxiety disorders. Left untreated, anxiety can last for a long time. It can become exhausting, debilitating and get in the way of us living our everyday lives. There are a range of effective treatments for anxiety, and you can get better. Visiting a doctor or a mental health professional is a good starting point when seeking help for anxiety.

Key points to remember

- Anxiety is normal, everyone experiences anxiety at some time.

- Anxiety becomes a problem when it interferes with your day to day life

- Anxiety disorders are a combination of psychological, physical and behavioural symptoms

- A range of factors can contribute to anxiety disorders

- Signs and symptoms of anxiety vary

Contact Us

Coolminds

Email: hello@coolmindshk.com

Black Dog Institute

Email: blackdog@blackdog.org.au

Resources

Seeking Help for Anxiety

This resource booklet has been localised for the Hong Kong context and translated to Traditional Chinese by Coolminds, a mental health initiative run by Mind HK and KELY Support Group. For more information on Coolminds, please visit www.coolmindshk.com

Thank you to the Black Dog Institute for donating their resources and for allowing us to adapt this. For the original version of this resource, please refer to the Black Dog Institute’s website: www.blackdoginstitute.org.au

What this fact sheet covers:

- Why seek help for anxiety?

- Who to talk to

- Treatment available

It’s important to get treatment for anxiety

Anxiety is physically and emotionally exhausting. Getting help early means you can start to get relief and recover sooner. There are many professionals who treat all kinds of anxiety.

There is a wide range of effective treatments for anxiety, e.g.

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

- E-mental health tools

- Relaxation techniques

- Medications

There are also lots of things you can do to help yourself.

Often, it’s a combination of things that help us get better, such as:

- A well-informed health professional you feel comfortable talking to

- The right psychological and medical therapies

- Support from family and friends

- Exercising and healthy eating

- Learning ways to manage challenges and stress, such as structured problem solving, meditation and yoga

How do I know it’s anxiety?

Severe anxiety can appear in ways that feel like other health issues, e.g.

- Chest pain

- A racing heartbeat

- Dizziness

- Rashes

Sometimes, anxious people think they’re having a heart attack.

When we’re anxious, we can also become hyper-aware of:

- Our body

- Aches and pains

- Perceived threats and danger

Sometimes, once we’re aware of a problem, we can become ‘hyper-vigilant’ in checking on all the discomforts and pains we feel. This can spiral into feeling more concern and worry, making the anxiety more severe.

You should always see a doctor, so they can make a thorough check of your symptoms and rule out any other medical condition.

Who can provide help for anxiety?

As well as your doctor, there are other health professionals who can help with anxiety, including:

- Psychologists

- Psychiatrists

- Counsellors

- School and university counsellors

- Social workers and occupational therapists trained in mental health

- Mental health nurses

What type of treatment is available?

There are three broad categories of treatment for anxiety:

- Psychological treatments (talking therapies)

- Physical treatments (medications)

- Self-help and alternative therapies

Psychological therapies are the most effective way to treat and prevent the recurrence of most types of anxiety. Depending on the type of anxiety, self-help and alternative therapies can also be helpful. They can be used alone or combined with physical and psychological treatments.

A thorough assessment by your doctor is needed to decide on the best combination of treatments for you.

Psychological treatments

Psychological treatments can be one-on-one, group-based or online interactions. Psychological treatments are sometimes called ‘talking therapies’ as opposed to ‘chemical therapies’ (i.e. medications).

Talking therapies can help us change habits in the way we think, and cope better with life’s challenges. They can help us address the reasons behind our anxiety, and also prevent anxiety from returning.

There are a wide range of psychological treatments for anxiety, including:

- Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)

- Exposure therapy (behaviour therapy)

- Interpersonal therapy (IPT)

- Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

- Positive psychology

- Psychotherapies

- Counselling

- Narrative therapy

Some of the above treatments can be accessed online. Evidence-based online treatments can be as effective as face-to-face treatments. These online treatments are often referred to as e-mental health programs.

Physical treatments

Your doctor should undertake a thorough health check before deciding whether medication is a good option for you. Taking medication for anxiety must be supervised by a doctor. If medication is prescribed as part of your treatment, your doctor should explain the reason for choosing the medication they’ve prescribed.

Your doctor will:

- Discuss the risks and benefits, side effects, and how regularly you need check-ups.

- Advise what treatments can work together with the medication, such as psychotherapy, lifestyle changes (e.g. exercise) and other support options.

Anti-anxiety medications are used for very severe anxiety in anxiety types such as:

- Panic disorder

- Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD)

- Social phobia

Anti-anxiety medications, such as benzodiazepines, can:

- Be addictive

- Become ineffective over time

- Have other side effects such as headaches, dizziness and memory loss

Anti-anxiety medications are not recommended for long-term use.

It’s important to know that not all anxiety needs medication. Many people respond well to lifestyle changes and psychological treatments.

Self-help and alternative therapies

There are a wide range of self-help measures and therapies that can be useful for anxiety. It’s good to know that there are things you can do for yourself to feel better.

Self-help and complementary therapies that may be useful for anxiety include:

- Exercise

- Good nutrition

- Omega-3

- Meditation

- De-arousal strategies

- Relaxation and breathing techniques

- Yoga

- Alcohol and drug avoidance

- Acupuncture

Different types of anxiety respond to different kinds of treatments. Severe anxiety may not respond to self-help and alternative therapies alone. These can be valuable adjuncts to psychological and physical treatments.

e-mental health programs

e-mental health programs can be used in conjunction with a mental health professional or as a stand-alone option. e-mental health programs (also called ‘e-therapies’ or ‘online therapies’) are online mental health treatment and support services. You can access them on the internet using your smartphone, tablet or computer. The programs can help people experiencing mild-to- moderate depression or anxiety.

Some e-mental health tools, such as myCompass developed by the Black Dog Institute, have been found to be as effective in treating mild-to- moderate depression as face-to-face therapies.

e-mental health treatments are based on face-to-face therapy, positive psychology and behavioural activation. These therapies mainly focus on reframing thoughts and changing behaviour.

Key points to remember

- Lots of professionals can help you with anxiety

- There are many types of treatments for anxiety, and you can get better

- Many people who have had anxiety have been able to seek help and live active, fulfilling lives

Contact Us

Coolminds

Email: hello@coolmindshk.com

Black Dog Institute

Email: blackdog@blackdog.org.au

Where to get more Information and Support

Black Dog Institute – “myCompass”

Student Health Services – “Understanding Anxiety Disorders”

OCD & Anxiety Support Hong Kong

Mind Hong Kong – “Anxiety and Panic Attacks”

The Mental Health Association of Hong Kong:

Phone: 2528 0196

Website: www.mhahk.org.hk

Resources

Helping Someone Who Has a Mental Illness: For Family and Friends

This resource booklet has been localised for the Hong Kong context and translated to Traditional Chinese by Coolminds, a mental health initiative run by Mind HK and KELY Support Group. For more information on Coolminds, please visit www.coolmindshk.com

Thank you to the Black Dog Institute for donating their resources and for allowing us to adapt this. For the original version of this resource, please refer to the Black Dog Institute’s website: www.blackdoginstitute.org.au

What this fact sheet covers:

- How to tell if someone has a mental illness

- What to do if you are concerned about a family member or close friend

- How to behave with someone who is depressed

- What to do if someone is suicidal

- Self care for carers

- Key points to remember

- Further information and support

Someone with a mood disorder is like anyone with any other illness – they need care and support.

Family and friends can provide better care if they are informed about the illness, understand the type of treatment and are aware of the expected recovery time.

How to tell if someone has a mental illness

Even if you know someone well, you will not always notice when they have changed. You are more likely to notice big or sudden changes but gradual changes can be easy to miss. It’s also true that people will not always reveal all their thoughts and feelings to their close friends and family.

For these reasons, family and friends cannot expect to always know when someone has a depressive illness and should not feel guilty that they ‘did not know’.

The best approach is to acknowledge that mental illnesses are common and to learn how to recognise the signs and how to offer help.

What to do if you are concerned about a family member or close friend

If you are worried that a family member or close friend has a mood disorder, try talking to them about it in a supportive manner and either suggest that they consult their doctor or another mental health professional.

Sometimes they may be reluctant to seek help. You might need to explain why you’re concerned and provide specific examples of their actions or behaviour that are worrying you. Providing them some information such as a book, fact sheets or helpful pamphlets might also help.

You could offer to assist them in seeking professional help by:

- Finding someone that they feel comfortable talking to.

- Making an appointment for them on their behalf.

- Taking them to the appointment on the day

- Accompanying them during the appointment if appropriate.

This level of help may be particularly appropriate if the person has a severe mood disorder such as psychotic depression or mania.

Young people, adolescents in particular, are vulnerable to mental health problems. If you are concerned about someone, try:

- Gently let them know you have noticed. changes and explain why you are concerned

- Find a good time to talk when there are no pressures or interruptions.

- Listen and take things at their pace

- Respect their point of view.

- Validate what they are experiencing, but don’t offer reassurance or advice too quickly

- Let them know that there is help available that will make them feel better.

- Encourage them to talk to a doctor or other health professional, and to find a trusted friend or family member that they can confide in.

There are also a range of services (e.g. telephone counselling and online resources) that are specifically designed for young people. You can find out more about what is provided in Hong Kong on the Coolminds website.

How to behave with someone who is depressed

Patience, care and encouragement from others are vital to a person who is experiencing depression. Someone experiencing depression is very good at criticising themselves and needs support from others, not criticism.

Clear and effective communication within the household or family is also important. Partners or families might find it helpful to see a psychologist during this time for their own support.

An episode of depression can provide an opportunity for family members to re-evaluate the important things in life and resolve issues such as grief or relationship difficulties.

Some Tips:

- Avoid suggesting to the person that they “cheer up” or “try to get over it”. This is unhelpful as it is likely to reinforce their feelings of failure or guilt.

- Another important part of caring is to help the treatment process – if medication has been prescribed, encourage the person to persist with treatment and to discuss any side effects with their prescribing doctor.

- The person may also need encouragement and help to get to their therapy appointments or complete any online therapy exercises they have been asked to do.

- During a depressive illness, counselling or psychotherapy often results in the person working through their life events and relationships; while this can be difficult for all concerned, friends and family should not try to steer the person away from these issues.

What to do if someone is suicidal

If someone close to you is suicidal or unsafe, try:

- Talking to them about it and encourage them to seek help.

- Remembering that if someone is feeling like their life is not worth living, they are experiencing overwhelming emotional distress.

- Helping the person to develop a safety plan involving trusted close friends or family members that can keep the person safe in times of emergency.

- Removing risks (e.g. take away dangerous weapons or items if that person is angry or out of control and threatening to disappear).

Self care for carers

(A carer is someone who provides support to a friend, family member, or neighbor in need of help because of their age, disability, or physical or mental health.)

- Carers are also likely to experience stress. Depression and hopelessness have a way of affecting the people around them.

- Therapy can release difficult thoughts and emotions in carers too. So, part of caring is for carers to look after themselves to prevent becoming physically run down and to deal with their internal thoughts and emotions.

- Treatment has a positive time as well; when the person starts to re-engage with the good things in life and carers can have their needs met as well.

Key points to remember

- If you are worried that someone is depressed or has bipolar disorder, try talking to them about it in a supportive manner and suggest that they see a mental health professional.

- If they don’t want to seek help, explain the reasons for concern and perhaps provide them with some relevant information.

- Young people are particularly vulnerable to depression.

- Patience, care and encouragement from others are all vital to the person who is depressed.

- If a loved one talks of suicide, encourage them to seek help immediately from a mental health professional.

- Depression can take a toll on carers and close family members – it is important for these people to take care of themselves as well.

Contact Us

Coolminds

Email: hello@coolmindshk.com

Black Dog Institute

Email: blackdog@blackdog.org.au

Where to get more help and support

Bilingual Web Resources

Mind Hong Kong – “Am I A Carer?”

Mind Hong Kong – “What Can Friends and Family Do To Help?”

Student Health Service – “Understanding Depression”

Student Health Service – “Emotional Health”

English-Only Web Resources

Reach Out: a web-based support for adolescents

Headspace online: help for young people

Bilingual Telephone Hotlines

Samaritans Hong Kong 24-hour hotline: 28960000

Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong 24-hour hotline: 23892222

Suicide Prevention Services 24-hour hotline: 23820000

Suicide Prevention Services “Youth Link” hotline (available 2pm-2am): 2382 0777

Hospital Authority Mental Health 24-hour Hotline: 2466 7350

Social Welfare Department Hotline: 2343 2255

Chinese-Only Telephone Hotlines

Youth Outreach 24-hour hotline service: 90881023

The Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups “Youthline” hotline (available Mon-Sat, 2pm-2am): 27778899

Resources

Depression in Adolescents & Young People

This resource booklet has been localised for the Hong Kong context and translated to Traditional Chinese by Coolminds, a mental health initiative run by Mind HK and KELY Support Group. For more information on Coolminds, please visit www.coolmindshk.com

Thank you to the Black Dog Institute for donating their resources and for allowing us to adapt this. For the original version of this resource, please refer to the Black Dog Institute’s website: www.blackdoginstitute.org.au

What this fact sheet covers:

- Signs of depression in adolescence

- Where to get help for an adolescent

- Key points to remember

- Where to get more information

Introduction

- A 2017 study by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups found that of the 3,441 secondary school and university students surveyed, 51% displayed symptoms of depression and close to 40% experienced high levels of stress (7 on a scale of 10).

- According to research done by the University of Hong Kong, more than two-thirds of Hong Kong’s university students experience symptoms of mild to severe depression.

- The HKJC Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention observed that suicide rates for full-time students increased by 76% between 2012 and 2016.

- Onset of depression is typically around mid-to-late adolescence, and it is important to recognise the early warning signs and symptoms. Early intervention can often prevent the development of severe depressive illness.

Developmental Impact

- The teenage years are a time when individuals develop their identity and sense of self.

- If depression is left to develop, it can lead to isolation from family and friends, risk-taking behaviours such as inappropriate sexual involvements and drug and alcohol abuse.

- It can also impact on school performance and study, which can have downstream effects on later career or study options.

- Both biological and developmental factors contribute to depression in adolescence. If bipolar disorder or psychosis is suspected, an assessment by a health professional is recommended. See our Fact Sheet “Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder” for more information.

Signs of depression in an adolescent

- An adolescent who is depressed may not show obvious signs of depression.

- It is often hard to distinguish adolescent turmoil from depressive illness, especially when the young person is forging new roles within the family and struggling with independence, and having to make academic and career decisions.

Signs of a depressed mood include:

- Lowered self-esteem (or self-worth)

- Changes in sleep patterns, that is, insomnia (inability to sleep), hypersomnia (excessive sleep) or broken sleep

- Changes in appetite or weight

- Inability to control emotions such as pessimism, anger, guilt, irritability and anxiety

- Varying emotions throughout the day. For example, feeling worse in the morning and better as the day progresses.

- Reduced capacity to experience pleasure: inability to enjoy what’s happening now, not looking forward to anything with pleasure such as hobbies or activities.

- Reduced pain tolerance: decreased tolerance for minor aches and pains

- Poor concentration and memory

- Reduced motivation to carry out usual tasks

- Lowered energy levels

Where to get help for an adolescent

- If you think someone you are close to might be depressed, you should encourage them to seek advice from a professional. (At school – school counsellor, social worker. Outside school – doctor, counsellor, psychologist)

- The first step is to speak to a professional who can conduct an assessment, provide options and discuss the next steps to take.

- Other initial sources of help are school counsellors and trusted close family members to whom the young person feels comfortable talking.

- If the young person does not want to seek help, it is best to explain your concerns and to provide them with some information to read about depression.