Resource Topics: supporting others/yourself

Resources

MythBuster – Trauma and mental health in young people: Let’s get the facts straight

Introduction

Most young people will have been exposed to at least one traumatic event in their lifetime. Multiple and prolonged exposure to trauma is also common. When a young person reaches out to open up about trauma, the way that others around them respond can have a massive impact on the young person’s ability to understand and cope with their experiences. Yet some aspects of trauma remain largely misunderstood, particularly its relationship with mental health.

This mythbuster has been created for young people, their families, and carers to replace some of the most common and harmful myths about trauma in the mental health space with a better understanding of what trauma is and how it can affect young people.

Trauma can come from many different life experiences

What is trauma?

Trauma is broadly described as a deeply distressing experience that can be emotionally, mentally, or physically overwhelming for a person. It takes on many different forms and effects vary from one person to another (van der Kolk et al., 2005; Bryson et al., 2017). It is important to know that an experience does not have to be life threatening to be traumatic. Approximately two thirds of young people will have been exposed to a traumatic event by the time they turn 16 (Copeland et al., 2007). Experiencing a traumatic event can potentially affect both their current and future mental health.

What types of events cause trauma?

Trauma can arise from many different life experiences. Some examples of different types of trauma are listed below:

Direct and indirect trauma

Some types of trauma are called ‘direct trauma’, and others are called ‘indirect trauma’ (May & Wisco, 2016). A ‘direct trauma’ is experienced first-hand or by witnessing a trauma occurring to another person. An ‘indirect trauma’ comes from hearing or learning about another person’s trauma second-hand.

Single event trauma

Single event trauma is related to a single, unexpected event, such as a physical or sexual assault, a fire, an accident, or a serious illness or injury. Experiences of loss can also be traumatic, for example, the death of a loved one, a miscarriage, or a suicide.

Complex trauma

Complex trauma is related to prolonged or ongoing traumatic events, usually connected to personal relationships, such as domestic violence, bullying, childhood neglect, witnessing trauma, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, or torture.

Vicarious trauma

Vicarious trauma can arise after hearing first-hand about another person’s traumatic experiences. It is most common in people working with traumatised people, such as nurses or counsellors. Young people may also experience vicarious trauma through supporting a loved one who is traumatised (e.g. a parent or a friend).

Trans- or intergenerational trauma

Trans- or intergenerational trauma comes from cumulative traumatic experiences inflicted on a group of people, which remain unhealed, and affect the following generations (Hudson, Adams & Lauderdale, 2016). It is most common in young people from refugee or migrant families.

Anyone can experience trauma, regardless of their age or social/cultural background

Who experiences trauma?

Some young people are at higher risk of being victimised, abused, marginalised, excluded, and/or experiencing unsafe situations that leave them vulnerable to potentially traumatic experiences. Young people who are more likely to have experienced trauma include those in out-of-home care, in the juvenile justice system, those experiencing homelessness, young refugees or asylum seekers, and young people working in emergency services (Orygen, 2017). However, it is very important to understand that anyone can experience trauma, regardless of their age or social/cultural background.

How do our perceptions of traumatic events change as we age?

When trying to understand the impact trauma has on the lives of young people, it is important to understand the way we make sense of and respond to trauma as we age. During childhood we are more sensitive to our environment, so how we view threats can be quite different to the way adults view threats (Odgers & Jaffee, 2013). For example, during COVID, parents may be distressed about the safety of their children, the loss of their livelihood, and the impact on their community. On the other hand, children may be most distressed about separation from their extended family and school friends, and the disruption of their daily routines (The Australian Child and Adolescent Trauma Loss and Grief Network, 2010). This can mean that adults might be confused or unable to relate to their child’s response to a traumatic event. Likewise, a child may also be confused by their parents’ reactions and/ or why they might not be feeling or responding to an event in the same way.

Young people and children process trauma differently

As their brains are still developing, children process trauma differently compared to adults. This means that the types of things that children interpret as traumatic, and how they understand them, can be very different to adults.

When looking back at traumatic experiences in childhood, it can be hard to understand the confusing emotions and reactions experienced at the time. A young person might look back and think that they should have been able to understand things ‘better’ or cope ‘better’. This can lead to strong and difficult feelings like anger, guilt, and shame.

When a young person is caught up in this way of thinking, they may cope with an ‘adult’ response. In other words, they attempt to look back on their experiences in childhood through the lens of an adult. By doing this, it is easy to forget that the trauma happened to a child, who has much less ability and life experience, to help them process their trauma and seek support.

The way we make sense of and respond to trauma changes as we age

How does trauma affect young people?

Short-term effects

The short-term effects of trauma are often described as normal reactions to abnormal events (Jones & Wessely, 2007), and can include:

- fear

- guilt

- anger

- isolation

- helplessness

- disbelief

- emotional numbness

- sadness, confusion

- flashbacks or persistent memories and thoughts about the event (van der Kolk, 2000)

It is really important to know that these are normal and healthy reactions to trauma. These can last for up to a month after the trauma has occurred, and can slowly reduce over time.

Long-term effects

Sometimes these strong emotions, thoughts, and memories can continue and even worsen over time. This can overwhelm a young person and have damaging effects on their life and course (e.g. their wellbeing, relationships, and their ability to work and/or study) (Orygen, 2017). Some traumas, such as those occurring in childhood, may have effects that only become clear later in life (Felitti, 2002). In the long-term, there is a strong relationship between trauma and poor mental and/or physical health outcomes; however, in many cases young people can bounce back with the right support (Iacoviello & Charney, 2014; Felitti et al., 1998). Additionally, in some situations, young people can draw personal strength from their struggle with trauma and experience a feeling of positive growth (Meyerson et al., 2011).

Developmental effects

Being exposed to trauma when individuals are very young can change how their brain grows and negatively affect their ability to learn (Whittle et al., 2013; Malarbi er al., 2017). Experiencing high levels of stress at a young age can also increase risk-taking behaviours in adolescence and early adulthood, which can lead to poor physical health later in life (Felitti, 2002).

What is post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD?

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the most commonly talked about trauma-related diagnosis. Symptoms include having intrusive memories of the traumatic event, increased stress, avoidance of situations and/or people associated with the trauma, and increased negative thoughts (American Psychiatric Society, 2013). These symptoms impact a person’s ability to keep up with their day-to-day life and make it hard for them to focus on work and/or study and other tasks.

In Hong Kong, an increase of people experiencing PTSD symptoms has risen to approximately more than 30% in 2019. PTSD can also cause problems with a person’s relationships with others (Koenen et al., 2017), and symptoms may differ between children, adolescents, and adults (Mikolajewski, Scheeringa & Weems, 2017). Thus, it is really important to get help early if you are struggling to cope after experiencing trauma because evidence shows that the sooner help is sought, the lower the risk of developing PTSD (Gillies et al., 2016).

Evidence shows that the sooner help is sought, the lower the risk of developing PTSD

What are the most common myths about trauma?

Traumatic events and a young person’s reaction to them vary a lot. They can vary between people (e.g. some people may be more sensitive to traumatic experiences than others), within the same person over time, or differ depending on the type of traumatic event the person has experienced.

This can make it difficult for us to have a shared understanding of what trauma is and how it can affect people. If we feel confused or uncertain about what trauma is and how it can affect someone, it would be very easy to end up believing in common and unhelpful myths instead.

Below are some of the common myths surrounding trauma and the reasons why these myths are harmful and untrue.

MYTH: “Everyone who has mental ill-health has experienced trauma”

This myth is particularly harmful because young people who have not experienced trauma, but who are struggling with their mental health may feel that they have no right to feel how they do, or become very confused about how they are interpreting their experiences. They may also worry that if they seek support, everyone would automatically assume they have experienced a type of trauma.

Just because a young person is experiencing mental ill-health, this does not necessarily mean that they have gone through trauma. There are many risk factors that contribute to the beginning of mental ill-health. These can be environmental, genetic, social, and cultural in nature (Kieling et al., 2011).

Mental ill-health can start without a specific event ‘tipping a person over the edge’. In fact, mental ill-health is often triggered by a build-up of a number of smaller stressful events rather than one big traumatic event (Fox & Hawton, 2004). Even though trauma is linked to a higher chance of poor mental health, it is important to remember that the causes of mental ill-health in young people are very complex and differ from person to person (Guina et al., 2017; Paus, Keshavan & Giedd, 2008).

It is really important to know that developing mental health problems after trauma is not a sign of weakness

MYTH: “Everyone who has experienced trauma will develop mental ill-health”

Most people who experience trauma do not develop mental ill-health as a consequence (Sayed, Iacoviello & Charney, 2015). Many factors influence whether or not a young person develops mental ill-health after experiencing trauma. These include the severity and type of trauma, the support available, how easily they can access this support, past traumatic experiences, family history, and physical health (Iacoviello & Charney, 2014; Sayed, Iacoviello & Charney, 2015; Brewin, Andrews & Valentine, 2000).

It is completely normal to experience strong or overwhelming emotions after a traumatic experience, but it is when these symptoms last a long time, worsen overtime, or cause other problems (e.g. using substances to cope) that mental health difficulties are likely to arise. It is really important to know that developing mental health problems after trauma is not a sign of weakness, nor does it reflect anything about you personally. It is simply a sign that you may need some extra support to recover from the effects of your experiences.

MYTH: “It’s my fault”

Trauma can happen to anyone, and if you are a victim of trauma, this does not mean that you are to blame for what happened to you. ‘It’s my fault’ is a common thought after experiencing trauma, and it is completely normal to feel shame, guilt, and/or self-blame after these experiences. Even though you may feel this way, it does not mean you deserve these feelings, and a huge part of recovery is working to overcome them.

These types of emotions are particularly common in young people who have been traumatised by another person (e.g. through sexual abuse, physical abuse, bullying, or violent crime). In cases of trauma resulting from abuse, it is important to understand that abuse comes from the needs and motivations of the perpetrator, not the individual. Being able to work through these strong emotions of self-blame, guilt, and/or shame is essential to recovery. This means it is very important to find the right help to support you through this process.

Traumatic events are sometimes singular and life threatening, but many are more complex.

MYTH: “Only bad things come out of traumatic experiences”

Struggling through traumatic experiences often changes the way a person views the world and people around them. A lot of the time, the changes in thoughts are negative (e.g. the world seems scarier, or people seem less trustworthy). However, in some situations, with the right support, and time to heal, a person may also draw strength and positive change from surviving a traumatic event.

When this happens, it is described as ‘post-traumatic growth’ (Linley & Joseph, 2004; Clay, Knibbs & Joseph, 2009; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). When someone experiences post-traumatic growth, they may gain a greater appreciation for life, a feeling of greater personal strength, a deeper connection to others, and even gain new ideas about the path they see their life taking in the future (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Research shows that post-traumatic growth is hugely influenced by many psychological, social, and environmental factors in a young person’s life (Meyerson et al., 2011). How each of us reacts to traumatic experiences is deeply linked to these factors, and our different reactions do not make us ‘weaker’ or ‘stronger’ compared to others.

MYTH: “Your life must be threatened for an event to be traumatic”

Traumatic experiences take many different forms (Weiss & Gutman, 2017). There does not have to be one defining event that makes something traumatic. It is true that traumatic events are sometimes singular and life threatening, but others are more complex. Many people experience trauma through ongoing or prolonged exposure to events such as abuse, neglect, and bullying. Others may experience trauma vicariously through encountering another person’s traumatic experiences first-hand.

MYTH: “PTSD is the most common response to trauma”

Although post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the most commonly talked about trauma-related mental illness, it is not the most common mental health diagnosis among people who have experienced trauma. There are many ways that trauma can affect mental health in young people (Sayed, Iacoviello & Charney, 2015). In fact, for most young people, PTSD only captures a small aspect of their mental health state after trauma (van der Kolk & Courtois, 2005). Young people who have experienced trauma can develop a wide range of mental health problems, without developing PTSD (Odgers & Jaffee, 2013). These can include depression (Widon, Du Mont & Czaja, 2007), anxiety (Fernandes & Osorio, 2015), complex PTSD (Resick et al., 2012), borderline personality disorder (Ball & Links, 2009), substance abuse disorders (Stevens, Murphy & McKnight, 2003), eating disorders (Pignatelli et al., 2017), psychosis (Bendall et al., 2008), and suicide-related behaviours (Miller et al., 2013).

Take home messages

- If you have experienced trauma, you are not alone. Trauma in young people is very common and it is important for family, friends, and mental health professionals to be aware of this.

- Traumatic events can be one off (e.g. car accident, sexual assault), ongoing/prolonged (e.g. childhood sexual abuse, bullying, emotional or physical abuse), or experienced second-hand (e.g. witnessing family violence). Any type of trauma has the potential to be very damaging to a young person’s mental health.

- Often young people who have been abused or neglected feel at blame for what has happened to them – they may feel it was their fault, or that they ‘brought it on’ or ‘asked for it’. If you are in this situation, it is very important to know that you are not to blame, no matter how strong the feelings of guilt or shame may be.

- There is no one uniform or ‘right’ way to respond to a traumatic event. Responses to trauma are highly variable. Different people may react very differently, even to the same situation.

- Young people experiencing mental ill-health have not necessarily experienced trauma, and this does not make their mental health difficulties any less ‘real’ or ‘legitimate’.

- Trauma does not always lead to mental ill-health in young people. Many young people exposed to trauma will make a full recovery without needing mental health intervention.

- Experiencing mental health difficulties related to trauma is not a sign of weakness or failure.

- Trauma can lead to a wide range of mental health difficulties, not just PTSD. These can include anxiety, depression, substance abuse, borderline personality disorder, and eating disorders. It is important to get support from a health professional for any of these difficulties.

- It is possible to recover from mental health difficulties related to trauma.

Help is at hand

Support is a huge protective factor against ongoing mental health difficulties related to trauma. Sometimes people can try to cope with the effects of trauma alone, even though reaching out for support can be hugely beneficial. Some young people might feel an overwhelming sense of self-blame or shame and might not be aware of or understand the effects of trauma, making it even harder to seek support.

Seeking help from someone you know

It is really important to try to find someone you can talk to about what’s going on for you. Seeking support for trauma recovery does not make a person ‘weak’, in fact it is a brave step to take on the road to recovery. Opening up about traumatic events can be daunting, making it very important to find someone you feel comfortable with and can trust to talk to. This person could be a family member, friend, or school counsellor.

Seeking professional help

Some young people may not feel comfortable opening up to people in their personal lives and may prefer to seek help through a mental healthcare professional. In terms of seeking professional help, a good place to start is with your doctor, a counsellor, or through a visit to your closest local support group.

A number of helplines in Hong Kong can be found here:

- Emergency hotline: 999

- The Samaritans 24-hour hotline (Multilingual): (852) 2896 0000

- Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2389 2222

- Suicide Prevention Services 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2382 0000

- OpenUp 24/7 online emotional support service (English/Chinese): www.openup.hk

More hotlines and resources can also be found here:

Want to know more?

Some helpful resources about trauma and its effects include:

- Asking for Help: When it’s time to talk about your mental health- Coolminds and Charlie Waller Memorial Trust (CWMT) UK factsheet

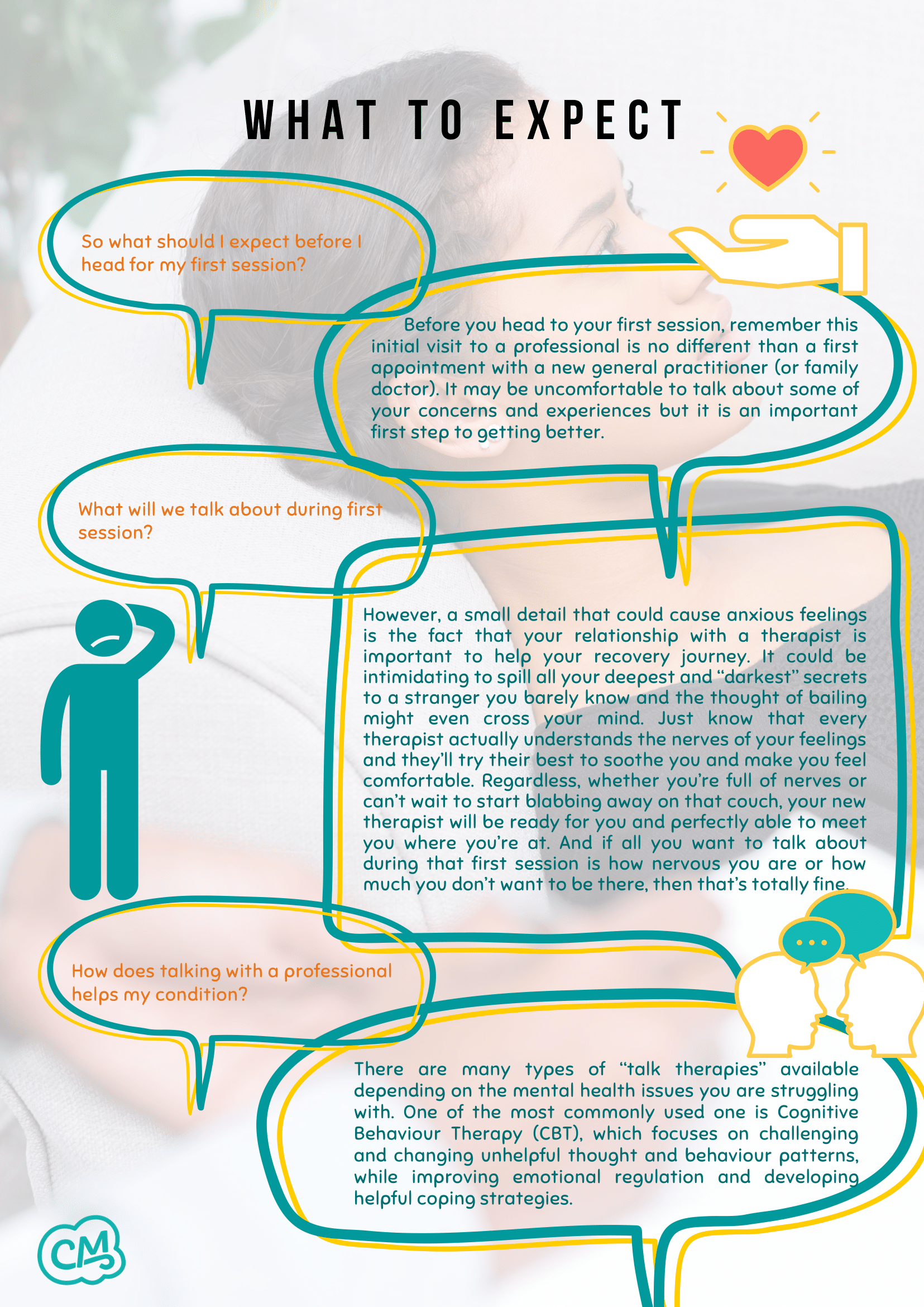

- Seeking help and what to expect- Coolminds factsheet

- Discrimination and Mental Health: A Guide for Young People- Coolminds factsheet

- Voices of Youth: Stigma, Discrimination and Mental Health- Coolminds factsheet

Supporting someone who has experienced trauma can be emotionally overwhelming, making it equally important to look after yourself. If you are concerned about the wellbeing of someone close to you, it is important to reach out for additional help.

Some highly recommended websites that offer more information on how to support to someone affected by trauma include:

- Samaritans Hong Kong

- Samaritans Befrienders Hong Kong

- The Zubin Foundation- Ethnic Minority Well-being Centre (EMWC)

- Christian Action (Woo Sung Centre)

- Yang Memorial Methodist Social Service- Yau Tsim Mong Family Education and Support Centre

- The Salvation Army Youth, Family and Community Services

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder – Institute of Mental Health Castle Peak Hospital

- BGCA – What is Trauma?

References

1. van der Kolk, BA, et al. 2005, ‘Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 18, no. 5. pp. 389–399.

2. Bryson, SA, et al. 2017, ‘What are effective strategies for implementing trauma-informed care in youth inpatient psychiatric and residential treatment settings? A realist systematic review’, International Journal of Mental Health Systems, vol. 11, pp. 36.

3. Copeland, WE, et al. 2007, ‘Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood’, Archives of General Psychiatry, vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 577–584.

4. Hudson, CC, Adams, S & Lauderdale, J 2016, ‘Cultural expressions of intergenerational trauma and mental health nursing implications for US healthcare delivery following refugee resettlement: an integrative review of the literature’, Journal of Transcultural Nursing, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 286–301.

5. May, CL & Wisco BE 2016, ‘Defining trauma: how level of exposure and proximity affect risk for posttraumatic stress disorder’, Psychological Trauma, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 233–40.

6. Orygen The National Centre of Excellence for Youth Mental Health, Youth Mental Health Policy Briefing: Trauma and Youth Mental Health. 2017, Orygen: Melbourne.

7. Odgers, CL & Jaffee SR 2013, ‘Routine versus catastrophic influences on the developing child’, Annual Review of Public Health, vol. 34, no. 1. pp. 29–48.

8. The Australian Child and Adolescent Trauma Loss and Grief Network 2010, ‘How children and young people experience and react to traumatic events’, Australian National University, Canberra.

9. Jones, E & Wessely S 2007, ‘A paradigm shift in the conceptualization of psychological trauma in the 20th century’, Journal of Anxiety Disorders, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 164–175.

10. van der Kolk, B 2000, ‘Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma’, Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 7–22.

11. Felitti, VJ 2002, ‘The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult health: Turning gold into lead’, Zeitschrift Fur Psychosomatische Medizin Und Psychotherapie, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 359–369.

12. Iacoviello, BM & Charney DS 2014, ‘Psychosocial facets of resilience: implications for preventing posttrauma psychopathology, treating trauma survivors, and enhancing community resilience’, European Journal of Psychotraumatology, vol. 5.

13. Felitti, VJ, et al. 1998, ‘Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 245–258.

14. Meyerson, DA, et al. 2011, ‘Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: a systematic review’, Clinical Psychology Review, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 949–964.

15. Whittle, S, et al. 2013, ‘Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology affect brain development during adolescence’, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 52, no. 9, pp. 940–952.

16. Malarbi, S, et al. 2017, ‘Neuropsychological functioning of childhood trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis’, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 72, pp. 68–86.

17. American Psychiatric Society 2013, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn, American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington.

18. Koenen, KC, et al. 2017, ‘Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health Surveys’, Psychological Medicine, vol. 47, no. 13, pp. 2260–2274.

19. Mikolajewski, AJ, Scheeringa, MS & Weems, CF 2017, ‘Evaluating diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, posttraumatic stress disorder diagnostic criteria in older children and adolescents,’ Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 374–382.

20. Gillies, D, et al. 2016, ‘Psychological therapies for children and adolescents exposed to trauma’, Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, vol. 10, pp. Cd012371.

21. Kieling, C, et al. 2011, ‘Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action’, The Lancet, vol. 378, no. 9801, pp. 1515-1525.

22. Fox, C & Hawton K 2004, Deliberate self-harm in adolescence, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London 23. Guina, J, et al. 2017, ‘Should posttraumatic stress be a disorder or a specifier? Towards improved nosology within the DSM categorical classification system’, Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 66

23. Guina, J, et al. 2017, ‘Should posttraumatic stress be a disorder or a specifier? Towards

improved nosology within the DSM categorical classification system’, Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 66

24. Paus, T, Keshavan, M & Giedd, JN 2008, ‘Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence?’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 947-57

25. Sayed, S, Iacoviello, BM & Charney, DS 2015, ‘Risk factors for the development of psychopathology following trauma’, Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 612

26. Brewin, CR, Andrews, B & Valentine, JD 2000, ‘Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults’, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, vol. 68, no. 5, pp. 748-66

27. Linley, PA & Joseph S 2004, ‘Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 11-21

28. Clay, R, Knibbs, J & Joseph, S 2009, ‘Measurement of posttraumatic growth in young people: a review’, Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 411-22

29. Tedeschi, RG & Calhoun LG 2004, ‘Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence’, Psychological Inquiry, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1-18

30. Weiss, KJ & Gutman AR 2017, ‘Testifying About Trauma: A Call for Science and Civility’, Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 2-6

31. van der Kolk, BA & Courtois CA 2005, ‘Editorial comments: Complex developmental trauma’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 385-388

32. Widom, CS, Du Mont, K & Czaja, SJ 2007, ‘A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up’, Archives of General Psychiatry, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 49-56

33. Fernandes, V & Osorio FL 2015, ‘Are there associations between early emotional trauma and anxiety disorders? Evidence from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis’, European Psychiatry, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 756-764

34. Resick, PA, et al. 2012, ‘A critical evaluation of the complex PTSD literature: implications for DSM-5’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 241-251

35. Ball, JS & Links PS 2009, ‘Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: evidence for a causal relationship’, Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 11, no. 1, pp 63-68

36. Stevens, SJ, Murphy, BS & McKnight, K 2003, ‘Traumatic stress and gender differences in relationship to substance abuse, mental health, physical health, and HIV risk behavior in a sample of adolescents enrolled in drug treatment’, Child Maltreatment, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 46-57

37. Pignatelli, AM, et al. 2017, ‘Childhood neglect in eating disorders: A systematic review and metaanalysis’, Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, vol. 18, no.1, pp. 100-115

38. Bendall, S et al. 2008, ‘ Childhood trauma and psychotic disorders: a systematic, critical review of the evidence’, Schizophrenia Bulletin, vol. 34, pp. 568-579

39. Miller, AB, et al. 2013, ‘The Relation Between Child Maltreatment and Adolescent Suicidal Behavior: A Systematic Review and Critical Examination of the Literature’, Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 146-172

Disclaimer

This information is not medical advice. It is generic and does not take into account your personal circumstances, physical wellbeing, mental status or mental requirements. Do not use this information to treat or diagnose your own or another person’s medical condition and never ignore medical advice or delay seeking it because of something in this information. Any medical questions should be referred to a qualified healthcare professional. If in doubt, please always seek medical advice.

Mythbuster writers

Anna Farrelly-Rosch

Dr Faye Scanlan

Youth contributors

Sarah Langley – Youth Research Council

Somayra Mamsa – Youth Research Council

Roxxanne MacDonald – Youth Advisory Council

Clinical consultant

Dr Sarah Bendall

First published as ‘Trauma and mental health in young people: Let’s get the facts straight’ by Orygen, 2018.

Resources

Excessive Exercise

Participation in regular physical activity is beneficial to both body and mind. It supports our body to grow stronger and our brain to work better. It relieves stress and anxiety and helps improve mood, concentration and memory.

However, when exercise becomes an obligation and you are experiencing negative consequences which put strain on your mind and body, there is a chance that you are exercising excessively, which can be a problem in itself, as over-exercising can bring serious negative impacts on health.

Why does it matter?

Excessive exercise affects both our physical and mental health. It could lead to potential injuries, due to overusing muscles or worsening previous injuries as your body is unable to recover fully. This could affect exercise performance in the longer term, especially among youth during this stage of physical development. Excessive exercise can also affect girls’ menstruation, as it directly and indirectly impacts hormonal changes in our bodies.

It can influence how you perceive your body, your self-esteem and it can be mentally taxing when our minds are preoccupied with the thoughts related to exercise. Excessive exercising can contribute to guilty feelings, or feelings of irritation and being on edge when you are not exercising. It also affects our daily lives and social relationship as we prioritise exercise over other matters.

Although it is not classified as a diagnosable mental health condition, over-exercising is often associated with multiple mental health conditions. Studies show that there is a link between excessive exercise, body dysmorphic disorder and eating disorders. It may also lead to or exacerbate existing mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and addiction.

Signs of excessive exercise

You may notice some of the following signs:

- Feeling prolonged muscle soreness and stiffness

- Feeling fatigued and tired, preventing you to maintain daily activities

- Feeling guilty for not exercising

- Constantly feeling the urge to exercise

- Finding your mind preoccupied with exercise and body image

- Using exercise as a key way to distract yourself from stress and anxiety

- Lower performance

- Unrealistically comparing yourself with others

- Often prioritising exercise over necessary tasks, social interactions and other urgent matters

Exercise is excessive and becomes a problem when it starts to affect your daily life and social relationships, or when it no longer brings you the benefits as originally intended. Reaching out to people you trust or seeking professional help can be useful.

What is the recommended amount of physical activity?

According to the World Health Organisation:

- Youth (aged 5-17) are recommended to do at least an hour of moderate to vigorous level of exercise per day. Adults are advised to undertake 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75–150 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week.

- Moderate level of physical activity – you can still talk, but you can’t sing, such as brisk walking and dancing

- Vigorous level of physical activity – you can only say a few words without stopping to catch a breath, such as running, hiking uphills, and jumping ropes

How can I take care of myself?

- Schedule rest days. Rest days are essential for your body to recover from exercising and strained muscles. It also lets you clear your mind from exercise and focus on other duties and work.

- Stick to an exercise schedule. Plan an exercise schedule that includes both active days and rest days.

- Take a break from exercise if you don’t feel like exercising. It is okay to take a break and let yourself recover from the accumulated stress from exercise – it can benefit you in the long run for your body and mind as they have time to recover to their optimal state.

- A healthy lifestyle is also crucial for your well-being as a whole. A healthy diet, sufficient rest and sleep also contribute to your physical and mental health. Learn more about maintaining a healthy lifestyle for your physical and mental well-being here.

- Talk to people you trust about your concerns. If you have concerns or struggle with over-exercising, talk to your friends, coach, teammates, or a family member you trust to see if alternatives are available. Talking to others is also a way to organise your thoughts and feelings.

- Engage in other activities. Engaging in other enjoyable activities can help focus on something else. If you find your mind is constantly occupied with exercise and related matters, try to immerse yourself in other enjoyable activities and enjoy the feeling that the new activity brings,

How friends and family can support

- Let them know you are worried and are there for them. If your loved ones show signs of excessive exercise that worry you, let them know that you care and are there to support and listen to them. Let them know that they are not alone.

- Acknowledge and validate their feelings and emotions. Different people hold different perspectives on things, and it is important to remember that all feelings and emotions are valid to their experiences. Avoid dismissing their worries and concerns, and try to understand their perspective.

- Don’t make assumptions. Excessive exercise can result from a mix of factors, don’t make assumptions about what drives them to exercise. Listening to them and understanding their perspective can encourage them to share more comfortably.

- Help them find useful information. Useful information such as maintaining overall wellbeing can encourage them to carry out healthy behaviours and avoid information that promotes unhealthy habits. It is also a way to show them that you care and are there to support them.

- Engage them in other activities. Spend time and engage in other enjoyable activities together, such as watching movies, online streaming, chatting and playing games.

Maintaining a healthy exercise habit can positively impact your life, both physically, mentally and socially – it is supposed to bring joy and relieve stress while keeping you physically healthy.

Reference

Trott, M., Yang, L., Jackson, S. E., Firth, J., Gillvray, C., Stubbs, B., & Smith, L. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of exercise addiction in the presence vs. absence of indicated eating disorders. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspor.2020.00084/full

World Health Organisation. (2020). WHO Guidelines on Physical Activities and Sedentary Behaviour. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/337001/9789240014886-eng.pdf.

Resources

Managing Disappointments Due to COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has come with many challenges, one of which has been experiencing grief due to loss. The pandemic measures may have resulted in disruptions to our daily routines; separation from our friends and family; the missing of milestone events (like graduations, birthdays, vacations). We may also find that we feel guilty because we are grieving losses that seem less important than the loss of life. But our feelings of grief over the disruptions of the pandemic are valid, our losses may not be as important as the loss of life but they matter to us.

How do I know if the losses are negatively affecting you:

- Often feeling irritable, frustrated, angry or resentful

- Low mood

- Feeling generally unmotivated

- Being preoccupied with thoughts about what you are missing out on

How to manage feelings of grief

Acknowledge your feelings of loss and grief and find ways to express your feelings of loss and disappointment

- Journaling

- Expressing yourself through art: drawing, painting, music or dance

- Talking to friends or family about how you feel, sharing your feelings of disappointment and your concerns

Incorporate new rituales to your routine to replace ones that have been cancelled or have been put on hold.

- Exercise

- An interesting online course

- An artistic hobby – creative writing, drawing/painting/sculpting

- Cooking or baking

- Volunteering – there are lots of great volunteering opportunities that can be done remotely

Find creative ways to celebrate milestone moments (like graduations, birthdays, anniversaries)

- Creating creative videos with your friends/family to celebrate the moment

- Sending gifts or care packages and opening them together online

- Virtual celebrations

What creative celebration method can you come up with? Think outside the box!

Stay present. During this time of loss we may find ourselves worrying about future losses which can increase our anxiety and our frustration. Here are some ways you can stay present

- Mindfulness can help us ground ourselves in the moment allowing us to appreciate and savour the enjoyment we are experiencing. When practising mindfulness try using all of your senses to anchor yourself in the present moment.

Look around and notice- 5 things you can see

- 4 things you can physically feel

- 3 things you can hear

- 2 things you can smell

- 1 thing you can taste

- Savouring, this means to live in the moment and appreciate the moment. Great ways to savour are by capturing moments we are enjoying (photographing/drawing/painting), or journaling what we are grateful for

Resources

Supporting Young People Through the 5th Wave

Supporting Young People Through the 5th Wave

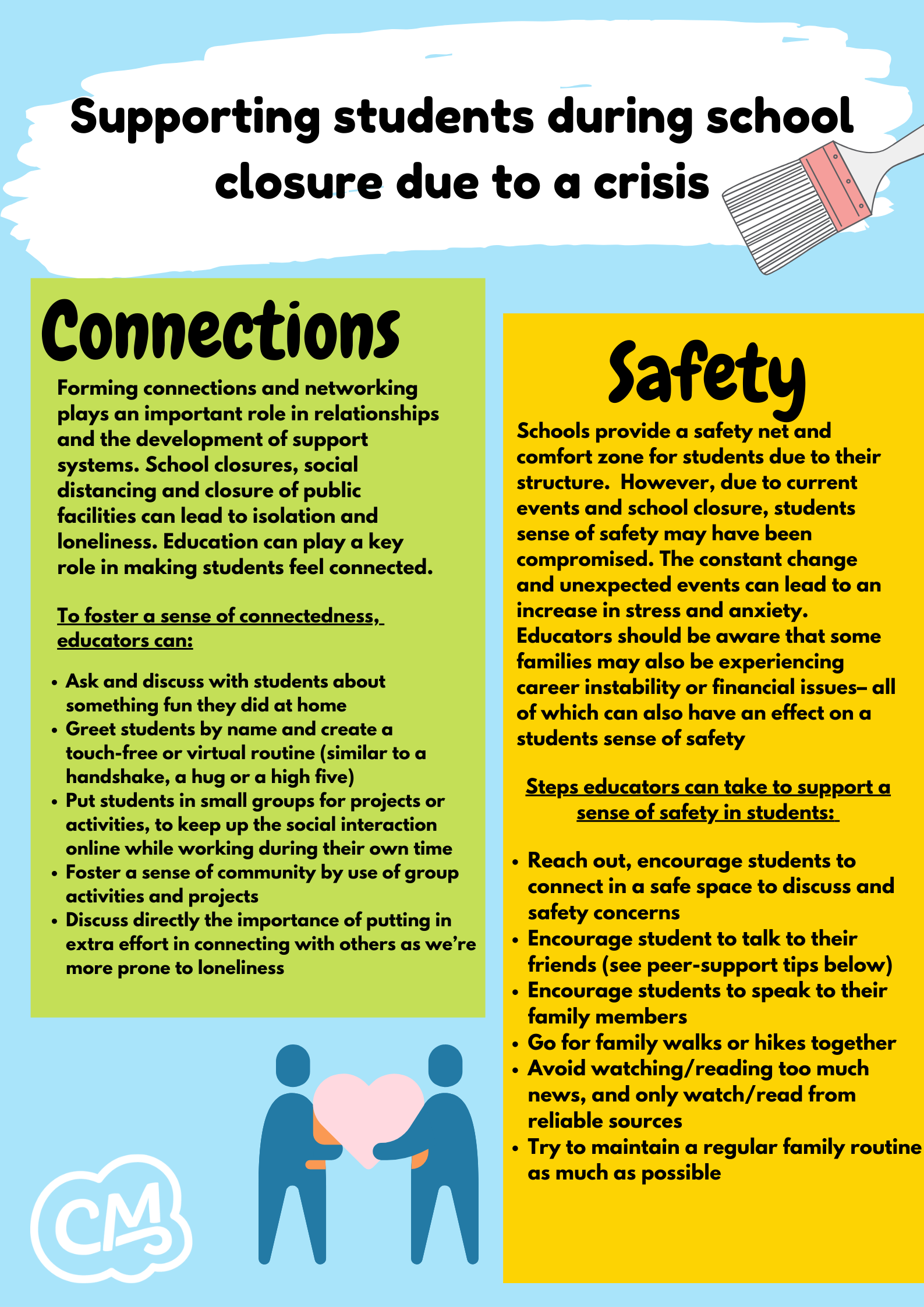

The current COVID-19 pandemic has been immensely disruptive to our young people; disruption to the school year and daily routines, separation from friends or family, postponement or cancellations of milestone events. Additionally, other stressors associated with the pandemic have been seen to negatively impact mental health wellbeing, such as uncertainty, alarming news feeds, and contradictory information. It is therefore important to help young people navigate these challenging times and foster resilience.

How to speak with your youth about the current situation

Start a conversation. Don’t shy away from talking about the challenges brought on by COVID19. Young people appreciate honest, open, non-judgemental conversations. What is unhelpful is to ignore or dismiss their concerns, this may drive them away from coming to you, and may lead them to seek answers and support on social media, which may not be as helpful and in some cases may be harmful.

Give them the space to explore how they are feeling and in turn how these feelings may be impacting the way they perceive the current situation as well as their behaviours, all in a non-judgemental environment.

Conversation starters:

“We are going through such difficult times, have you noticed any impacts on how you are feeling?”

“I have noticed that you have been down lately, is there anything you would like to talk about?”

“What is the hardest thing for you these days?”

Validate. Validate their feelings, showing them that you understand how difficult this has all been for them. Letting them know that “it’s ok to feel [sad/frustrated/angry] right now” can also help open a conversation about healthy ways to cope with these feelings. What is essential is to first listen to their concerns without jumping to solutions. Allow them to explore their feelings and letting them be heard first, before any exploration of solutions.

Provide reassurance. Discuss their specific concerns and provide reasurancess when possible. Exploring with them (it is important that this is something you do with them rather than telling them what to do) any strategies they can engage in to keep them safe and healthy. I.e. if they are concerned about getting infected, you can speak to them about helpful health supporting behaviours like washing hands, wearing a mask. This allows them to see that while some things are out of their control there are many things that are within their control.

Self-compassion. Reminding them to be gentle and kind to themselves. When we struggle we may have feelings of self-blame and self-criticism. Reminding them that these are challenging times and you are doing the best you can.

New routines. Encourage them and work with them to set a regular routine, replacing any cancelled/postponed activities with new engaging activities, and including health supporting behaviours such as:

- Regular bedtimes

- Exercise

- Connecting with friends and loved ones

- Engaging in a hobby or activity they are passionate about

Managing anxiety during COVID

The current pandemic has provoked anxiety in many people. While some anxiety can motivate us to protect ourselves and help keep us safe, if anxiety is not managed well it can impact day to day functioning.

Signs that a young person is struggling with anxiety:

- Preoccupation with their fears/worries

- Maladaptive coping behaviours (i.e. avoidance, substance reliance)

- Physical symptoms associated with their anxiety (which have been assessed by a GP but do not have physical origin) – i.e. headaches, muscle tension, pain, stomach discomfort

Supporting young people experiencing anxiety

Supporting young people who are experiencing anxiety will be through helping them to explore and recognise their anxious thoughts, validating their feelings and supporting them to engage in coping strategies. Supporting them to explore more measured ways to look at the situation. However, if they are having difficulties with this and their anxieties, seeking professional help will be helpful (more details on seeking professional support can be found at the end of this article)

Strategies:

- Help them to think of evidence to support their anxious thoughts and evidence that challenge their anxious thoughts. This will allow them to find a balance in their thinking and will help them challenge their anxieties

- Explore with them more optimistic ways of thinking about their situation – what is the upside

- Encourage them to practice mindfulness or grounding techniques which help bring us back to the present moment

Coping with isolation & low mood

The isolating nature of social distancing and school disruptions can lead to low mood and possibly depression, if helpful coping strategies are not used. Social contact and friendship development is an important developmental milestone in the adolescent years. Social connection disruption impacts both mood and healthy social development.

Signs that a young person is struggling:

- Low mood

- Further isolation, avoiding contact with friends

- Maladaptive coping behaviours (i.e. avoidance, substance use, self harm)

- Physical symptoms associated with their low mood (which have been assessed by a GP but do not have physical origin) – i.e. generalised pain, stomach discomfort

Supporting young people experiencing low mood

- Encourage them and support them to connect with friends and loved ones

- Allowing for more time on-line (within reason) on social platforms or gaming platforms that allow them to connect with their friends

- This is also a good time to speak to them about staying safe on-line

- Allowing for safe in-person meeting (within the limitations of social distancing guidelines)

- Help them set manageable expectations. Understanding that “good enough” and accomplished is better than perfect but not achievable, particularly during times of challenge

- Support them to explore hobbies or activities they can take up, to help them feel fulfilled and give them a sense of mastery and accomplishment

Seeking professional help

It is important to recognise when professional help is needed; such as speaking to a counsellor or psychologist to process experiences or engage in structured talk therapy. Many therapists are offering services virtually or have safety guidelines to help facilitate in-person therapy. To learn more about seeking mental health supports in Hong Kong follow the link here

How do I know a young person needs professional help?

- They are increasingly withdrawn, isolated or disengaged, and not responsive to coping strategies

- Engaging in self harm, substance reliance, or expressing suicidal thoughts

- Significant disruptions to their daily activities and engagement with the world around them due to their anxiety or mood

If you are concerned about safety or think your young person needs emergency supports please see the list of emergency services here

Taking care of yourself is essential during this time. You will not be able to effectively support others if you are struggling. The strategies above apply to your self-care as well, so ensure you are engaging in healthy coping strategies, this will also model healthy behaviours to the young person you are supporting.

Resources

What is Meditation?

What is mindfulness meditation?

- Mindfulness meditation is simply dropping down into our body & feeling the sensations of our body & our changing emotions.

- We are simply being present with what is going on inside us.

- We are anchoring ourselves in our present. Our thoughts no longer drive us to the past or the future, instead, we are fully living here.

Why is meditation important?

- Allows us to understand our mind and take control of it instead of having it control us. It brings inner peace and self awareness.

- Allows us to be present: to be aware of what is happening here and now: in our thoughts, our emotions, our bodies.

- Allows us to stop identifying with our thoughts and emotions.

- We have space to CHOOSE how to react, to CHOOSE the story we tell about ourselves.

How often should I practise?

- Start with a short meditation every day, five minutes of sitting down in the morning.

- Once you have a consistent habit, you may start to slowly increase the time you meditate for.

- Constancy over quantity

Benefits of mindfulness meditation

- Meditation helps you break out of negative thought patterns by giving you clarity.

- It can bring the simple peace and joy of being present, as you are less likely to repeat negative reactive patterns.

- The same way we have body hygiene, we need to have mental hygiene, to keep not just our body clean but our mind too.

- It is not just a personal responsibility but a collective one. When you centred and balanced within your mind, you spread that peace with everyone you meet through your own behaviour.

Resources

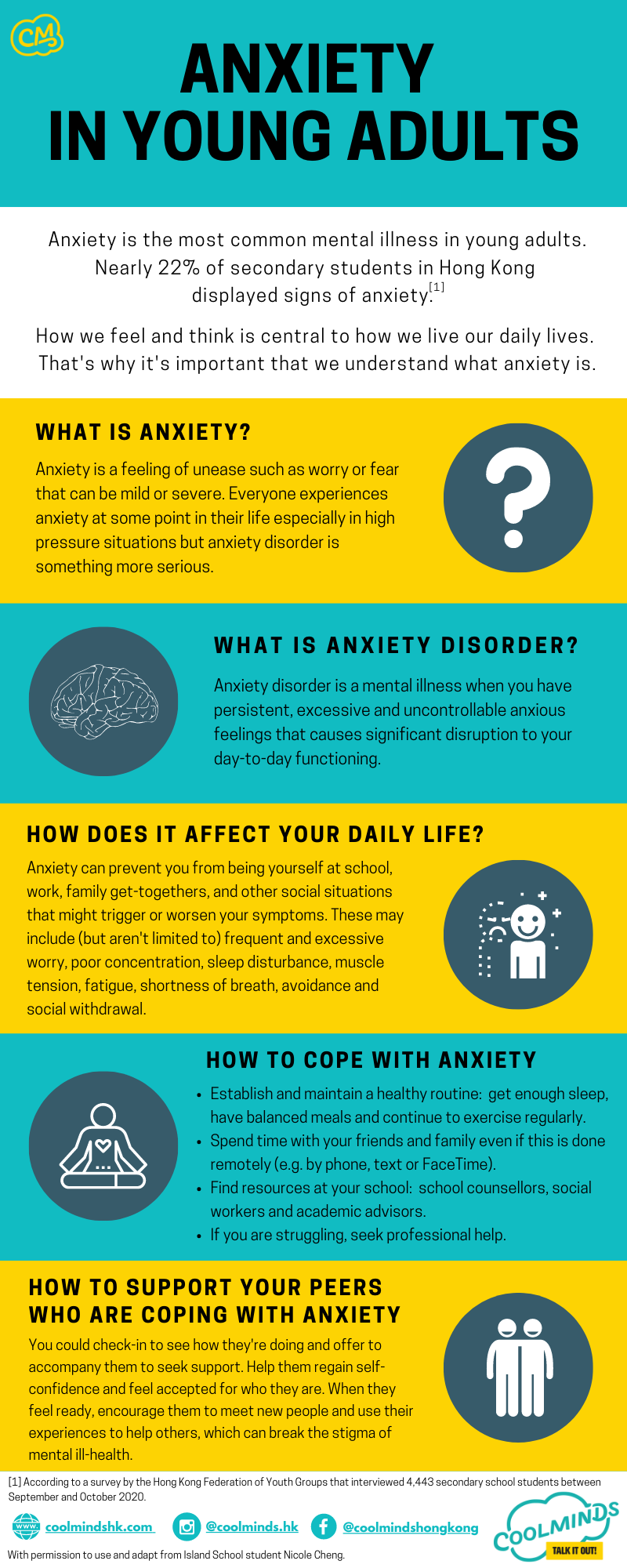

Anxiety in Young Adults

Anxiety is the most common mental illness in young adults.

According to a survey by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups that interviewed 4,443 secondary school students between September and October 2020, nearly 22% of secondary students in Hong Kong displayed signs of anxiety.

How we feel and think is central to how we live our daily lives. That’s why it’s important that we understand what anxiety is.

What is anxiety?

Anxiety is a feeling of unease such as worry or fear that can be mild or severe. Everyone experiences anxiety at some point in their life especially in high pressure situations but anxiety disorder is something more serious.

What is anxiety disorder?

Anxiety disorder is a mental illness when you have persistent, excessive and uncontrollable anxious feelings that causes significant disruption to your day-to-day functioning.

How does it affect your daily life?

Anxiety can prevent you from being yourself at school, work, family get-togethers, and other social situations that might trigger or worsen your symptoms. These may include (but aren’t limited to) frequent and excessive worry, poor concentration, sleep disturbance, muscle tension, fatigue, shortness of breath, avoidance and social withdrawal.

How to cope with anxiety?

- Establish and maintain a healthy routine: get enough sleep, have balanced meals and continue to exercise regularly.

- Spend time with your friends and family even if this is done remotely (e.g. by phone, text or FaceTime).

- Find resources at your school: school counsellors, social workers and academic advisors.

- If you are struggling, seek professional help.

How to support your peers who are coping with anxiety?

You could check-in to see how they’re doing and offer to accompany them to seek support. Help them regain self-confidence and feel accepted for who they are. When they feel ready, encourage them to meet new people and use their experiences to help others, which can break the stigma of mental ill-health.

Special thanks to Island School student Nicole Cheng who granted permission to use and adapt her work.

Resources

Parents’ Guide to Navigating COVID-19

Efforts to stem the spread of COVID-19 through public health measures such as social distancing and self-isolation have taken a toll on Hong Kong’s youth. With prolonged school closures, many youth have increased their screen time and reduced their physical activity as well as face-to-face social interaction, which can contribute to low mood and loneliness. Changes in routine combined with the anxiety and stress associated with a new and unknown virus can lead to changes in behavior.

As a parent, it may be stressful to take care of both your own and your children’s mental health and wellbeing. This booklet aims to discuss how you, as a parent, can support your kids as well as yourself during these difficult times.

Talk it out

Talking to your young person about what is going on and why can help relieve some tension from both your and their minds. If you have noticed changes in your teenager, gently let them know what you have noticed and let them know there is no judgement. This is especially important to build trust. As parents, you are probably busier than ever, trying to manage work, home learning and other responsibilities. Therefore, it’s important to make a conscious effort to keep the lines of communication open.

Timing

Find a good time to talk, when you feel in a good headspace to do so and will be unlikely to be interrupted. If it’s not the right time, let your child know that you want to give them your full attention, and let them know when that will be.

Honesty

Be honest about what is happening in the world, and share only the facts to avoid unnecessary worries. It’s OK to say you don’t know the answer to a question and follow-up with the information later on or explain that there are many unknowns right now. Helping your teenager learn to sit with uncertainty is an important life lesson.

Active listening

Ensure that you are really listening to what they say, and let the conversation progress at their pace. Be a good listener, communicate that you respect their point of view, and validate what they are experiencing and their feelings. Remember, you can validate their experience even if you don’t agree with it or feel the same way. Offering reassurance or advice too quickly can have the opposite effect. Instead, focus on the idea of ‘listening without fixing’.

Shared resources

Let them know that there is help available and encourage them to talk to a doctor, other health professional, friend or family member if they need it. Do share a list of services designed specifically for young people in Hong Kong, which you can find on the Coolminds website.

Missed opportunities + Handling grief

Young people will likely face a lot of disappointments during this time such as missed school, parties, graduation, visiting universities, sports, and competitions for which they have prepared. As some of these are important milestones, it’s crucial to acknowledge these losses and the impact they have.

Let them know that it’s OK to feel angry, sad and frustrated, this may actually help them accept the disappointment.

Reassure them they are not alone and that, during this confusing time, many have been impacted and are also grieving for the losses caused by the pandemic.

Missing out on these types of events can also cause anxiety and low mood, so it is important to be on the look-out for that.

Here are some tips to help your young person cope with these losses:

- Stay connected

Find ways for them to stay connected to their friends. You may consider relaxing screen time rules to allow for this.

- Engage in personal expression

Journaling, drawing, painting, playing music, and dancing among others.

- Practising self-care

Ensure they get enough sleep and exercise, consider introducing meditation and/or yoga.

- Challenge negative thoughts

Reframe negative thoughts that might be out of proportion with less extreme and more realistic ones.

- Enjoying the wins

Some aspects of the situations such as missing classes they don’t like or activities they do not enjoy may be welcomed at this time, allow them to appreciate and celebrate these small “wins”.

- Continue the conversation

Don’t just check-in once, do so periodically as feelings and thoughts may change.

You might also feel a sense of sadness and grief at missing important milestones in your children’s lives. It is important to take the time to recognize your own disappointment and practise self-validation by acknowledging that these feelings are fair and valid despite seemingly bigger issues in the world. Take the time to grieve for these losses.

Youth mental health

It is important to understand that the measures we have to use to protect us from COVID-19 can impact our mental health. The fear of getting infected, uncertainty about the future, and all of the changes we’ve made to our routines can cause feelings of anxiety, while social distancing measures can lead to feelings of isolation and low mood. This is true for all of us and even more pronounced for those who have struggled with their mental health before the outbreak. It is therefore important to pay attention to your child’s mental health and wellbeing.

Normalise anxiety

Explain to them that anxiety is a natural feeling to have when there is a threat present, as is the case right now.

Discuss their perspective on the dangers involved and ensure that they are not overestimating the gravity of the situation or underestimating their ability to take care of themselves and manage difficult things.

Focus on strengths

Remind them that they are resilient and able to navigate tough situations. Remind them of different ways in which they have done so in the past.

Limit news exposure

Encourage youth to limit the amount of time they spend reading and watching information on COVID-19.

Remind them to refer only to reputable sources for updates.

Encourage helpful distractions

Such as watching movies, playing games, exercising and talking to friends. These can be used at times of distress or boredom.

Keep communication channels open

Encourage teenagers to discuss any concerns with family and friends.

Make sure that you are managing your own anxiety!

It’s possible that your kids are feeding off of you. If you are feeling particularly stressed, find someone to talk to or engage in an activity that usually helps you relax or calm down.

Youth may be especially frustrated with social distancing measures if some of their friends’ families are not participating in it. Explain that your family is doing what experts recommend and suggest that they blame you when telling their friends that they can’t go out. Remain open to suggestions as to how they can be social while remaining safe. Consider relaxing screen time rules to allow kids to connect with their friends online given they can’t always do it in person. At the same time, ensure that digital connecting does not replace in-person interactions with family, sleep or studying.

Don’t forget to give them time and space! Youth still need their privacy and alone time, especially with the increased togetherness created by working from home and no school. Don’t take it personally if they prefer to spend more time in their room, and do not give them a hard time about it as long as they are completing their school work and other responsibilities.

Self-care

Remember, in order to take care of your young person well, you need to take care of yourself first. Working from home or the office and trying to manage youth at home as well as home learning is hard. You may not be as efficient as you normally are. You may also feel you are not being the best parent you can be.

Be kind to yourself and give yourself a break, everyone is learning to navigate this new way of life, and it takes time to adapt and get things right. Keep in mind that spending more time together is not the same as the quality, focused time you probably have when you and your young person are accomplishing daily tasks separately.

Some self-care ideas include:

- Make time to switch off from responsibilities and duties every day. Read a good book or watch TV.

- Allow only a certain amount of time each day to learn about COVID-19 updates from reputable sources.

- Engage with family and friends on the phone, Facetime, Zoom, Whatsapp, etc.

- Schedule a date night with your partner or quality time alone with a friend at least once a week.

- Practise mindfulness. There are many free apps available to support mindfulness if you are unsure of how to do it.

This is also a time of uncertainty with regards to jobs and financial stability, which can cause high levels of stress and anxiety. Seek support from family and friends where possible. There are also some government sources that can be helpful.

Physical health

Exercise can boost our immune system but it also boosts our mood, our concentration, our confidence, and improves our sleep. Encourage your young person to engage in some form of physical activity every day. It is equally important for parents to do the same. This can be an opportunity to spend fun, non-stressful time together.

Get outside! Go for a run, bike ride or long walk. Take advantage of the many free exercise videos available online and through apps. Play video dance games and use virtual sports simulators. Use what you have in the environment around you to engage in physical activity. Getting your endorphins flowing will be beneficial for everyone.

It is also important to maintain a consistent sleep schedule to ensure you and your child get enough rest. Try your best to eat a healthy diet and drink plenty of water.

Home Learning

Home Learning is challenging for youth, parents and teachers alike. There are equipment and internet requirements to successfully engage in home learning. If you do not have access to these resources, talk to your school about how they can help you and your teenager accomplish what you need.

It is important to remember that your teenager is probably a lot more capable than you realise and can manage much of what they need to do on their own. Make sure to give them that credit and the opportunity to show you that they can do it.

Helpful tips: Routines & Schedules

- Draft a daily schedule together – make sure to get your teenager’s input instead of directing them. Empower them to be responsible for their time, which should allow them to get their school work done in addition to being “social” and engaging in other activities that are important to them.

- Try to use non-controlling, non-directive language to ensure teenagers are accomplishing what they need to, while communicating that they are still in control of their time. A good example of that is asking, “what is your plan today?” Agree on an amount of checking-in that is acceptable to both you and your youth. One idea is to schedule a window of time each day to check-in and provide any assistance that may be needed.

Try not to get stuck in thoughts about how you think youth will react and notice how they are managing. If they are acting more maturely than they have in the past, give them the autonomy to manage on their own accordingly.

Remember that most youth around the world are in a similar position. Your kids will most likely not be further behind others because of home learning. In addition, teachers are experts at managing such situations. They will help your child catch up when school resumes if necessary. For those who have kids graduating from secondary school or University, keep in mind that this is a global pandemic. Universities and employers are fully aware of the challenges faced during this time and the resulting repercussions for everyone. Keep in mind that this is not forever, kids will go back to school!

Use the extra time well!

Although the situation is far from ideal, families rarely get to spend this much time together so do not forget to enjoy it! Make time to do fun things together that you normally don’t have the time to do such as cooking, baking, playing board games, teaching a new skill, etc.

Give your closets and cabinets a good clear out, and donate things you no longer need to charity. Take the time to learn a new skill yourself. Take online classes if you are interested in a career change or to support your current line of work.

Most of all remember to look after yourself and your kids. Your mental and physical well-being are more important during this time than getting all of the school work done or being an exemplary employee. If you are feeling financially unstable, make use of government resources. If you or your kids are not able to maintain good mental health during this time using the suggestions provided, it’s important to seek professional help.

Emergency support

If you are experiencing strong levels of distress or trauma which are interfering with your life, remember that you do not have to face it alone, and that help is available.

For emergency support, please contact the hotlines below:

Emergency hotline: 999

The Samaritans 24-hour hotline (Multilingual): (852) 2896 0000

Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2389 2222

Suicide Prevention Services 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2382 0000

OpenUp 24/7 online emotional support service (English/Chinese): www.openup.hk

More support services can be found here: https://www.coolmindshk.com/en/emergency-hotlines/

More non-urgent support services can be found here: https://www.coolmindshk.com/en/communitydirectory/

Resources

Voices of Youth: Stigma, discrimination and mental health

Interviews with Khadeeja Khan and Zuhaa Khan, Coolminds Youth Summit Ambassadors, and Zita Marie Puentespina, a Year 10 student

What are your thoughts on how ethnic minorities view mental health, and how is this topic discussed?

Zita: Sadly, many ethnic minorities come face to face with the idea that mental health may be a taboo subject in their upbringing. Moreover, umbrella terms such as “being difficult” or “dramatic” may come into play. This helps delay an individual’s understanding of “mental health” and how they can healthily overcome it.

Khadeeja: I think ethnic minorities lack awareness when it comes to mental health. For many, if you cannot see it then it is not there. It is easier to visit a doctor for a bruise you have on your arm than visit the doctor for bruised emotions. In the ethnic minority community, mental health is seldom talked about and that only worsens it further. Common issues like post-natal depression in women are hardly ever discussed because the majority do not even know what it is and many do not know how to deal with it. Although the youth are a lot more open to this, parents can be ignorant to talk or even learn about mental health.

Name-calling and shaming with words like ‘mad’ , ‘crazy ’ , ‘attention-seeker’ are common in the minority community. Whilst doing my Psychology degree, I was faced with the same issues as it was considered a subject with ‘no future’ and ‘a waste of time’. So, while the youth are learning about mental health and are opening themselves up, the older ones are still closed off and driving the generation gap further apart. This is mainly because in the countries where the ethnic minority immigrants come from, mental health is a taboo, making it difficult for them to comprehend.

Zuhaa: Unfortunately it’s not prioritised and thrown under the radar for the most part, in my opinion. Until it becomes a visible issue (e.g. drug abuse and dependency). Depression, trauma, anxiety are often viewed as “excuses” and “acts of laziness” so the ones struggling from these challenges are far from receiving help in their own community. Success and making a name out of yourself is constantly deemed significant. As painful and discouraging as this may be, your status and success are measured by your bank balance and the number of properties you own in the EM community. There isn’t much talk about what’s going on in your head and the significance of emotional discomfort.

Issues with racism and discrimination reflect back to one’s identity. In the case of an immigrant child, the “sense of belonging” and “need for assurance ” are parts of life that the “average” local is provided with but immigrant children struggle to find. The use of labels and a lack of acceptance, appreciation, and respect can harm mental health and cause long-term detrimental effects on individuals.

As for personal experience, fortunately mine have been subtle compared to what others may have experienced. That said, hearing about troubling tales in your community can hurt your own mental health too. It adds to the emotional stress of constantly thinking “what this place, what do people presume of me” simply based off appearance, ethnic features, clothing etc.

What are some barriers for ethnic minorities who want to seek help?

Khadeeja: The main barrier is independence – many people live with their parents until they get married, so wanting to seek help under the guardianship of their parents would be difficult especially when the parents are not willing to agree or accept their mental health. Additionally, there is the issue of acceptance. Seeking help and being vulnerable would mean that they accept they are going through something and would have to be vocal about it, yet they have been taught to do the opposite their whole lives. Confidence plays a barrier too. When parents, family and society have told them to stay quiet and avoid their feelings, finding the confidence to speak out is hard and will need a lot of perseverance and support. Finally, confidentiality and trust is a huge barrier. Many ethnic minorities in Hong Kong are usually somehow acquaintances, friends or related to each other in other ways. The insecurity of information being ‘leaked’ to their parents, relatives etc discourages the youth and minorities as a whole about speaking up.

Zita: A barrier I believe is quite evident is the “communication barrier” as this does have an instant strain in one’s ability to express themselves and be fully understood. Although an EM may try their best to express their need for help, the receiving person may not understand them, despite the effort the EM may be showing. Due to prevalent language, cultural and inter-generational barriers, I believe acts of compassion and love should be shown louder.

How can we best support mental health for everyone despite cultural differences?

Khadeeja: We can make the ethnic minority community a safe place for them to open up. We can provide a platform for them which would empower them and help them. When other people from different backgrounds come together and speak out, it helps to de-stigmatize mental health and they can feel accepted and validated. We need to realise that although we may have different cultures, backgrounds and religions, the one thing that we can all connect with is our emotions and feelings. Education is vital too, and this should start from schools, which would then be brought to homes. Before I started my Psychology degree, I had minimal information about mental health. My education means that I can help others to get educated too. If we target 100 people, for example, we might not reach out to all of them but even if 50 parents can be educated on mental health, it may be enough to increase support around mental health for at least some people in our community.

Zita: We must have a constructive foundation in which a collection of knowledge about mental health is addressed and shared, this may be in different forms of media. This may be a place where individuals can share their own ideas and tailor the given resources to their own cultural backgrounds, as mental health should not take away from one’s culture but should be understood positively in the context of their culture.

Zuhaa: It’ s crucial to place significance on an individual’s culture since cultural influence does play a role in shaping one’s life. But we need to just set our differences aside and provide a set of ears to those who come to seek help. The fact is that there’s little to no emphasis on mental health in the community, all that there is is the constant denial of mental health as a health issue. This makes it so hard to speak up.

How can youth support other youth who have been victims of racism or discrimination?

Zuhaa: Remind them that it’s not their fault. Often times the discriminatory words and phrases used are a reflection of the racist himself. It’s a problem that is bred in the racist’s mind instead of the victim. At the end of the day, the victim needs to accept that it’s impossible to change one’s ethical features, the culture and custom they were born in. Spending more time in understanding one’s own culture and dwelling on its importance to the advances of the world are far better alternatives than constantly being hard on oneself because of an unfortunate encounter with racism. If possible, also advise the victims to be patient and try their best to spread awareness on what’s wrong and what shouldn’t be said to people from a different race, etc.

Khadeeja: Youth can support other youth who have been victims of racism and discrimination by speaking up about their own experiences. It’s that simple! We need advocates, ambassadors and supporters who can speak up about their own mental health experiences and this will encourage others to do the same. We need societies, groups and events by youth for youth and mental health Coolminds Youth Summit is a prime example of that! The youth can also just contribute their time to mental health charities and organisations and attend the events. The presence of youth at such occasions is enough to encourage other youth to get involved.

Zita: We must acknowledge their experiences, create a safe place for self-expression, and use these experiences to inform the immediate people around them in order to spread awareness. We must create a platform of understanding where people can become informed and then empowered to make a difference.

The lives of people with mental health conditions are often embedded by stigma as well as discrimination.

Stigma is a reality for many people with a mental illness, and they report that how others judge them is one of their greatest barriers to a complete and satisfying life.

Where to Get More Support

A List of Community Resources

Government Departments:

Support Service Centres for Ethnic Minorities – a list by the Race Relations Unit of the Home Affairs Department.

Integrated Children and Youth Services Centres – provide social work intervention for children and youth 6-24.

Integrated Community Centres for Mental Wellness – provide community support, social rehabilitation services, clinical assessment and treatment for those aged 15 or above and their family members or carers.

Government-funded Non-Profit Making Organizations (NPOs):

Christian Action SHINE Centre: Self-help and Mutual-help Groups for ethnic minorities who encounter social and economic problems.

Hong Kong Christian Service CHEER Centre: Counselling, guidance and referral services are provided by registered social workers for all ethnic minorities in Hong Kong and all organisations serving ethnic minorities, to facilitate their swift settlement in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong Community Network LINK Centre: Registered social workers offer counselling or referral to appropriate government department or agencies. Specially trained ethnic minority staff offer translation services.

International Social Service: Counselling and Guidance services for ethnic minorities with HKID cards.

New Home Association HOME Centre: Individual and mutual support for all ethnic minorities in Hong Kong.

Yuen Long Town Hall Support Service Centre for Ethnic Minorities: Provides counselling and referral service to pertinent organizations, offers emotional support, and gives sessions on problem-solving and stress management skills for Hong Kong ethnic minority residents aged 9-27.

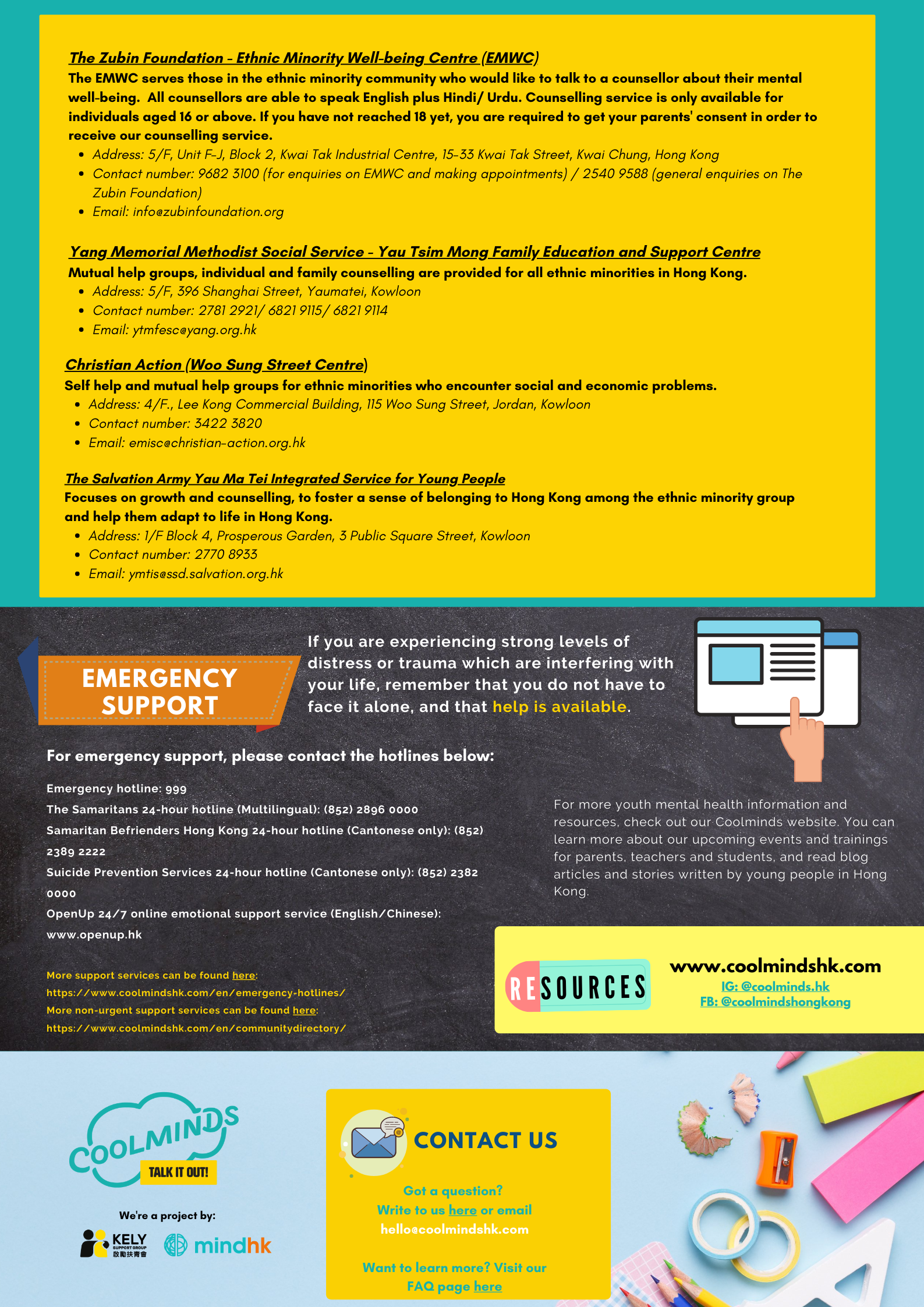

The Zubin Foundation – Ethnic Minority Well-being Centre (EMWC)

The EMWC serves those in the ethnic minority community who would like to talk to a counsellor about their mental well-being. All counsellors are able to speak English plus Hindi/ Urdu. Counselling service is only available for individuals aged 16 or above. If you have not reached 18 yet, you are required to get your parents’ consent in order to receive our counselling service.

- Address: 5/F, Unit F-J, Block 2, Kwai Tak Industrial Centre, 15-33 Kwai Tak Street, Kwai Chung, Hong Kong

- Contact number: 9682 3100 (for enquiries on EMWC and making appointments) / 2540 9588 (general enquiries on The Zubin Foundation)

- Email: info@zubinfoundation.org

Yang Memorial Methodist Social Service – Yau Tsim Mong Family Education and Support Centre

Mutual help groups, individual and family counselling are provided for all ethnic minorities in Hong Kong.

- Address: 5/F, 396 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kowloon

- Contact number: 2781 2921/ 6821 9115/ 6821 9114

- Email: ytmfesc@yang.org.hk

Christian Action (Woo Sung Street Centre)

Self help and mutual help groups for ethnic minorities who encounter social and economic problems.

- Address: 4/F., Lee Kong Commercial Building, 115 Woo Sung Street, Jordan, Kowloon

- Contact number: 3422 3820

- Email: emisc@christian-action.org.hk

The Salvation Army Yau Ma Tei Integrated Service for Young People

Focuses on growth and counselling, to foster a sense of belonging to Hong Kong among the ethnic minority group and help them adapt to life in Hong Kong.

- Address: 1/F Block 4, Prosperous Garden, 3 Public Square Street, Kowloon

- Contact number: 2770 8933

- Email: ymtis@ssd.salvation.org.hk

Emergency support

If you are experiencing strong levels of distress or trauma which are interfering with your life, remember that you do not have to face it alone, and that help is available.

For emergency support, please contact the hotlines below:

Emergency hotline: 999

The Samaritans 24-hour hotline (Multilingual): (852) 2896 0000

Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2389 2222

Suicide Prevention Services 24-hour hotline (Cantonese only): (852) 2382 0000

OpenUp 24/7 online emotional support service (English/Chinese): www.openup.hk

More support services can be found here: https://www.coolmindshk.com/en/emergency-hotlines/

More non-urgent support services can be found here: https://www.coolmindshk.com/en/communitydirectory/

Resources

Discrimination and Mental Health – A Guide for Young People

Introduction

Hong Kong is a very multicultural city with a melting pot of cultures. In the last 10 years, the number of non-Chinese ethnic people living in the city has increased by over 70%.

Did you know that ethnic minorities constitute 8% of Hong Kong’s population?

There are over half a million ethnic minorities living in Hong Kong.

72.2% of ethnic minorities aged 14 and below and 51% of ethnic minorities aged 15-24 were born in Hong Kong.

It’s important to understand that not everyone shares the same views and upbringing. What we see in the news, movies, social media, or books may present a very narrow or one-sided view of specific cultures. Diversity can help us work more productively in teams and foster creativity as there are lots of positive things we can learn from each other.

Learning about other cultures helps us understand different perspectives within our communities. It helps us challenge harmful stereotypes and personal biases about different groups. We can grow in understanding and learn to respect other “ways of being” that are not necessarily our own.